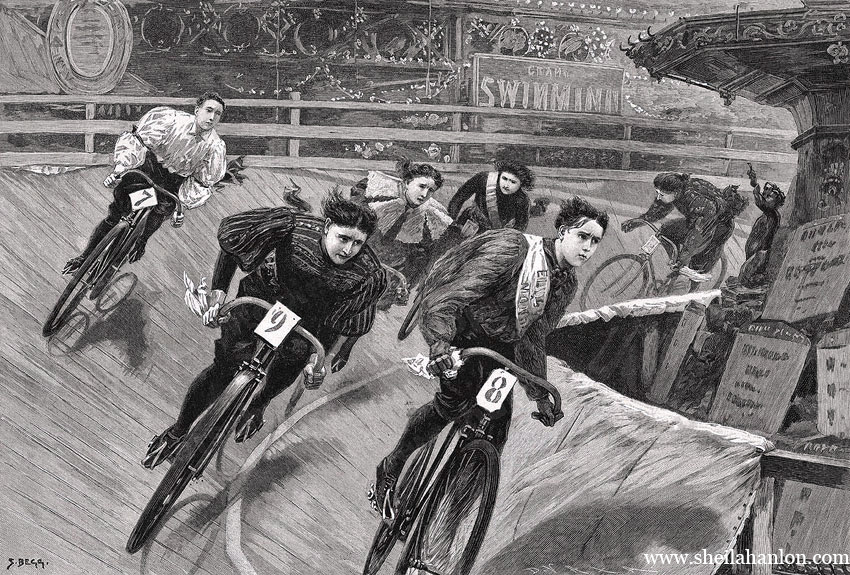

S.Begg, Lisette takes the lead at The Royal Aquarium, 1896

S.Begg, Lisette takes the lead at The Royal Aquarium, 1896

On November 18th, 1895 novice racer Monica Harwood, a young woman from Buckinghamshire who had only learned to bicycle six months earlier, took her place on the track at The Royal Aquarium. It was day one of a wildly anticipated twelve days’ of ladies racing, and the race was about to start. Chief among the stars of the track were French and English champions Mdlle Lisette Marton and Miss Grace respectively, fierce rivals accomplished cyclist who promised a close competition.

The race had a surprise ending in store. The favourites to win had their chances dashed by accidents on the track and an unbeatable performance from young upstart Harwood who was about to make a name for herself as a champion racer. The spectators who turned out in droves to see the lady cyclists at The Royal Aquarium witnessed the emergence of a new, though only briefly popular and profitable, form of women’s cycling that blurred the lines between sport and and entertainment.

On one hand, the ladies cycling races held at The Royal Aquarium in 1895 and after were a form of entertainment not dissimilar to the gymnastic and theatrical shows performed by women at pleasure gardens and cheap theatrical venues of the time, but on the other they marked a milestone in the recognition of women’s cycling as a professional sport, international contest and profitable commercial venture.

This post explores the context, press reaction, and gender politics of the ladies’ cycle races held at The Royal Aquarium, a short-lived enterprise that was part sport and part spectacle within the spectrum of late Victorian culture.

Sport or Spectacle: Victorian Women’s Cycle Racing in Context

“The ladies’ twelve days cycle races,” as the competition was billed, was promoted as the first event of its kind held in Britain. The series was certainly the first multi-day women’s track races to captivate the public imagination. Daily play-by-play reports of the action ran in newspapers throughout the duration of the races, including The Times, Standard, Daily News,and Lloyds Weekly, and magazines covered them as both cycling and entertainment news. Press and magazine coverage painted a vivid picture of the ladies’ races as a mix of athletics and amusement. The competition attracted sold-out audiences, mostly composed of men curious to see the novel, dangerous, and voyeuristic spectacle of women cycle racers. The Queen magazine for 28 December 1895 confirmed that “Quite a number of notabilities have been to see the racing at the Aquarium, which has proved such a success that it is to be continued, while as much as a guinea is asked for the best seats.”

“The ladies’ twelve days cycle races,” as the competition was billed, was promoted as the first event of its kind held in Britain. The series was certainly the first multi-day women’s track races to captivate the public imagination. Daily play-by-play reports of the action ran in newspapers throughout the duration of the races, including The Times, Standard, Daily News,and Lloyds Weekly, and magazines covered them as both cycling and entertainment news. Press and magazine coverage painted a vivid picture of the ladies’ races as a mix of athletics and amusement. The competition attracted sold-out audiences, mostly composed of men curious to see the novel, dangerous, and voyeuristic spectacle of women cycle racers. The Queen magazine for 28 December 1895 confirmed that “Quite a number of notabilities have been to see the racing at the Aquarium, which has proved such a success that it is to be continued, while as much as a guinea is asked for the best seats.”

The twelve day racing series was the most prominent part of a larger program of ladies’ cycle races held at the Royal Aquarium in 1895.”A total of 29 days of women’s racing took place between November 18 and December 31 1895, with further races beginning in January 1896. The twelve days’ of racing was divided into several events, rather that being one continuous race, starting with a six day race. The competition was international, attracting riders from France, Belgium, England, Scotland and as far afield as Canada. Most of them were experienced racers with their eye on cash prizes, though there were a few novices like Harwood. The six day race that opened the event, held from November 18th-30th, was the most popular event on the program. It garnering tremendous press attention and attracting sold out crowds in its final days. The racers registered to compete were divided into two sections of ten riders, each of which ran two races per day, one mid day and the other in the evening. The first run was generally 3-3.5 hours, and the second run 1.5-2 hours. Competitors’ daily mileages were added to their totals as the race progressed, with the greatest aggregate distance on the final day determining the winner.

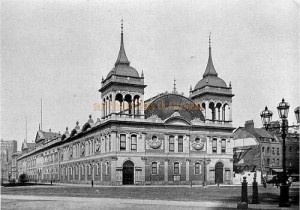

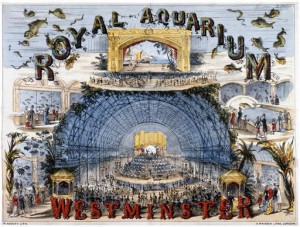

The inclusion of ladies’ cycle races in The Royal Aquarium’s program reflects the late-nineteenth century perception of women’s cycling as something novel with taboo undertones within Victorian culture. Cycling was a relatively new pastime, with women only taking up the pastime en mass in the mid 1890s as the safety bicycle invented in the mid 1880s became readily available on the mainstream market and cycling became a popular leisure fad. The Royal Aquarium was a well known entertainment venue, which by the mid 1890s when it hosted ladies cycle racing, was in the business of presenting a rough class of popular amusement. When it first opened in 1876, however, it had much nobler aspirations as a cultural institution. The Royal Aquarium and Winter Garden, shown left from a photo near its time of opening found in Harold P. Clunn’s The Face Of London (1956), was built on a grand scale on Tohill Street next to Westminster Abbey. It was designed by Alfred Bedborough as a successor to The Crystal Palace and a venue for intellectual entertainment such as art exhibitions, classical concerts, and plays. These forms of high culture, however, quickly proved unpopular. Management soon turned to variety acts to bring the crowds needed to make ends meet. The Royal Aquarium’s reputation may have crumbled, but it remained, nonetheless, an impressive structure both inside and out. The exterior of the building featured stately Portland stone. It’s main hall, where the cycling track was erected, measured 340 feet by 160 feet. Soaring glass and iron cathedral ceilings resembled those of the Crystal Palace and the palm houses at the Royal Botanical Gardens. The interior was decorated with palm trees, fountains and classical sculptures to create an enlightened atmosphere. Smaller rooms off the central hall offered more intimate surroundings for eating, smoking, reading, chess and art appreciation. The complex was also home to a theatre, skating rink, art gallery, and thirteen massive aquarium tanks. Unfortunately, a mechanical fault rendered the marine facilities unusable. They were left empty for the duration aside from the exhibit of a dead whale in 1877, an incident which became a comic short hand for The Aquarium’s reputation as a grand failure.

The inclusion of ladies’ cycle races in The Royal Aquarium’s program reflects the late-nineteenth century perception of women’s cycling as something novel with taboo undertones within Victorian culture. Cycling was a relatively new pastime, with women only taking up the pastime en mass in the mid 1890s as the safety bicycle invented in the mid 1880s became readily available on the mainstream market and cycling became a popular leisure fad. The Royal Aquarium was a well known entertainment venue, which by the mid 1890s when it hosted ladies cycle racing, was in the business of presenting a rough class of popular amusement. When it first opened in 1876, however, it had much nobler aspirations as a cultural institution. The Royal Aquarium and Winter Garden, shown left from a photo near its time of opening found in Harold P. Clunn’s The Face Of London (1956), was built on a grand scale on Tohill Street next to Westminster Abbey. It was designed by Alfred Bedborough as a successor to The Crystal Palace and a venue for intellectual entertainment such as art exhibitions, classical concerts, and plays. These forms of high culture, however, quickly proved unpopular. Management soon turned to variety acts to bring the crowds needed to make ends meet. The Royal Aquarium’s reputation may have crumbled, but it remained, nonetheless, an impressive structure both inside and out. The exterior of the building featured stately Portland stone. It’s main hall, where the cycling track was erected, measured 340 feet by 160 feet. Soaring glass and iron cathedral ceilings resembled those of the Crystal Palace and the palm houses at the Royal Botanical Gardens. The interior was decorated with palm trees, fountains and classical sculptures to create an enlightened atmosphere. Smaller rooms off the central hall offered more intimate surroundings for eating, smoking, reading, chess and art appreciation. The complex was also home to a theatre, skating rink, art gallery, and thirteen massive aquarium tanks. Unfortunately, a mechanical fault rendered the marine facilities unusable. They were left empty for the duration aside from the exhibit of a dead whale in 1877, an incident which became a comic short hand for The Aquarium’s reputation as a grand failure.

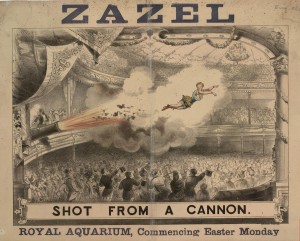

By the time the ladies cyclists took to the track, The Royal Aquarium’s reputation as a place of ill repute was firmly established. Its halls were said to crawl with single young ladies looking for male companions, at a price for their company of course. It was also a place where the lowest form of entertainment awaited spectators at a cheap price. Included in the ticket price for the 1895 lady cycle races at The Royal Aquarium was a packed bill of entertainments performed in the rooms adjacent to the main event, which spectators could dip in and out of at will. Most highly recommended was the Human Horse, who promised to amaze onlookers by playing the harmonium, reading, writing and performing addition, subtraction, and multiplication “with accuracy.” (Curiously, accurate division was not listed.) The Daily News claimed this equine miracle possessed “human intelligence,” while The Morning Advertiser called the act “really marvelous.” There were also dancing elephants, ballerinas, an attractive girl called “The Human Arrow” who was shot from a giant bow, flying and mid-air feats, eccentric knock-abouts, fire dancers, serio-comics, a boxing kangaroo, Japanese performers, conjurers, mandolin players, a man hatching from an egg, swimming performances, The Harrison Lady Acrobats, and countless other variety acts. Those curious to see women riding bicycles, especially in revealing costumes, could take in the Lady Dunedin Trick Cyclists in addition to the women’s cycle races on the main stage. The Royal Aquarium also hosted men’s cycle races, though as Aquarium manager Mr Ritchie, explained “As men’s races were no novelty, I put on the ladies races first and they were an instantaneous triumph.” (“How Ladies Races are Managed,” The Hub, 1896)

Velodrome racing reached its height of popularity around 1895-98. Races took place on both permanent tracks, some of which had been around since the 1880s, and temporary tracks specially devised in the 1890s for use in exhibition halls like The Royal Aquarium and Olympia Hall. Moving races off the road and into velodromes transformed the nature of cycle racing and transformed it into a mass spectator sport. Cycle enthusiasts had long experimented with race formats and innovative ways to test their personal abilities. Six day races first emerged for men in the 1870s, growing popular in the US in the 1880s and 1890s, and emerging in Europe and the UK soon after, with women’s versions beginning during the cycling craze of the late 1890s. Women’s cycle racing pre-dates the late Victorian era when they became part of popular entertainment, but it had always been conducted on the margins of sport. One of the earliest recorded appearances of female velocipede racers dates to 1868, when four women entered a race in Bordeaux, the illustration of which shown left emphasizing their bare legs appeared in Le Mode Illustre. Women’s racing may have been more popular in the 1890s, but their competitions were not sanctioned by racing bodies such as the International Cycling Union until much 1893. Even then, women’s races were only held sporadically and without the professional recognition granted to that men’s races. Women’s cycle races were generally relegated to the status of novelty acts and light entertainment, as they were at The Royal Aquarium, rather than respected as sports competitions.

Velodrome racing reached its height of popularity around 1895-98. Races took place on both permanent tracks, some of which had been around since the 1880s, and temporary tracks specially devised in the 1890s for use in exhibition halls like The Royal Aquarium and Olympia Hall. Moving races off the road and into velodromes transformed the nature of cycle racing and transformed it into a mass spectator sport. Cycle enthusiasts had long experimented with race formats and innovative ways to test their personal abilities. Six day races first emerged for men in the 1870s, growing popular in the US in the 1880s and 1890s, and emerging in Europe and the UK soon after, with women’s versions beginning during the cycling craze of the late 1890s. Women’s cycle racing pre-dates the late Victorian era when they became part of popular entertainment, but it had always been conducted on the margins of sport. One of the earliest recorded appearances of female velocipede racers dates to 1868, when four women entered a race in Bordeaux, the illustration of which shown left emphasizing their bare legs appeared in Le Mode Illustre. Women’s racing may have been more popular in the 1890s, but their competitions were not sanctioned by racing bodies such as the International Cycling Union until much 1893. Even then, women’s races were only held sporadically and without the professional recognition granted to that men’s races. Women’s cycle races were generally relegated to the status of novelty acts and light entertainment, as they were at The Royal Aquarium, rather than respected as sports competitions.

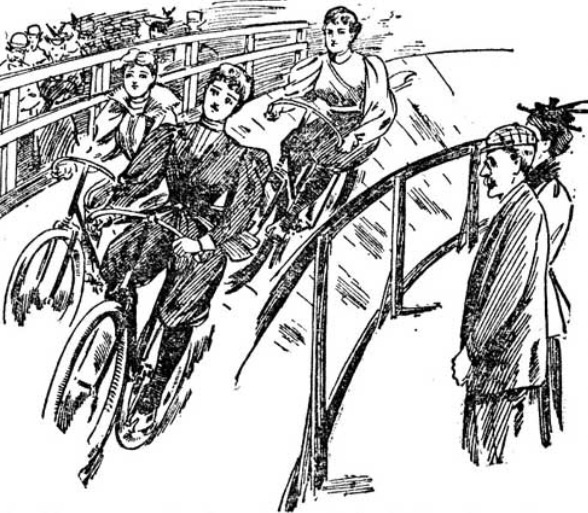

The track erected in The Royal Aquarium in 1895 captured the attention of the press. The custom built but hastily erected wooden track occupied the entire main hall of the building. It covered 11,300 feet in area and each lap equaled one tenth of a mile. (Standard 21 Nov 1895). Lloyds Weekly News for 24 Nov 1895 described the track as constructed from pine planking fastened to joists, fenced in by railings, and raised 6 feet above the inner track at the banked east and west ends. “This ‘banking up’ as it is called,” the paper explained, “though giving the track a rather strange appearance to those unaccustomed to seeing it, is absolutely essential if great speed is to be attained, and with a little practice the riders go round the ends without the slightest diminution of speed, though they have to hang over and incline their machines towards the center at the sharp angle depicted in our sketch.” Though considered a technical marvel by some, others declared the track dangerous, including the majority of the cycling press. Following the injury of two riders in a spectacular crash during the 1895 women’s six days’ race, The Queen suggested the safety standards for women’s races were irresponsibly lax, asking “Why do not the authorities inspect such tracks as these, and forbid dangerous contests? Any racing man would have condemned this track. It ought to have been at least twice as wide, the corners ought to have been of a much greater radius, with the banking carried further into the straights. The size–ten laps to the mile–is far too small.”

Trackside Play-by-Play: The Ladies’ Six Day Race in Action

Twenty racers was well over overcapacity for The Royal Aquarium track, so the lady cyclists were divided into two sections of ten riders each. The first section to start included Mdlles Nellie La Touche, Aboukaia, Solange, Marie Cannoe (or Cannoc), Henrietta Palliarde, Lucie Latrielle and Misses Clare Gamble, Rosa Blackburn, Lilian Adaire, and Benham. The second section was considered the race to watch, since it featured the French and English champions Lisette Marton and Clara Grace. Also in this section were Mdlles Fanoche Vautro, Beanny Vautro, Marcelle Vautro, Eteogella, Reillo and Misses Ellen Hutton, Monica Harwood, and Rosina Lane. The racers wore colours to distinguish themselves. French riders Solange, Latrielle and La Touché all sported black. Lisette was also in black, but stood out in her sash. Cannoe wore white and grey, Gamble rode in fawn and light blue, Blackburn chose brown and pink, Harwood wore black and gold with a white collar, and Benham wore green with a red cap. In the photograph from The Queen shown left, Harwood is the rider in the back row closest to the center behind the rider in stripes. Lisette is easy to pick out in her tri-coloured sash.

Twenty racers was well over overcapacity for The Royal Aquarium track, so the lady cyclists were divided into two sections of ten riders each. The first section to start included Mdlles Nellie La Touche, Aboukaia, Solange, Marie Cannoe (or Cannoc), Henrietta Palliarde, Lucie Latrielle and Misses Clare Gamble, Rosa Blackburn, Lilian Adaire, and Benham. The second section was considered the race to watch, since it featured the French and English champions Lisette Marton and Clara Grace. Also in this section were Mdlles Fanoche Vautro, Beanny Vautro, Marcelle Vautro, Eteogella, Reillo and Misses Ellen Hutton, Monica Harwood, and Rosina Lane. The racers wore colours to distinguish themselves. French riders Solange, Latrielle and La Touché all sported black. Lisette was also in black, but stood out in her sash. Cannoe wore white and grey, Gamble rode in fawn and light blue, Blackburn chose brown and pink, Harwood wore black and gold with a white collar, and Benham wore green with a red cap. In the photograph from The Queen shown left, Harwood is the rider in the back row closest to the center behind the rider in stripes. Lisette is easy to pick out in her tri-coloured sash.

The action accelerated in time with the first riders as they set off with a burst of energy and got up to speed quickly on Day One. According to The Star, 21 Nov 1895 at “Exactly twenty minutes past two, the signal was given and the ladies started off, bending over the handles of their little safeties for the first few yards, then quickly straightening themselves they made a splendid pace amongst the enthusiastic cheers of a large crown. Trouble set in early for Miss Benham in her red cap, who touched the balustrade rounding the east curve of the track and came off her machine. Unhurt, she quickly scrambled back on her machine. At 3:00, Mdlles Palliarde and La Touch countered while rounding the east curve, forcing them both off their bikes after which, though unhurt, they left the track for some time. Others also fell, but remounted and continued the race. Miss Benham brought down several other racers after the first accident to herself, and “her style of riding was such as to cause much excitement amongst the French ladies, who shouted at her frantically when she was near them. The umpire ordered her off the track for erratic riding at the 8 mile mark. The French riders were in no position to complain about Benham’s riding, since they too contravened racing regulations by adopted an unfair riding strategy. The Star explained that “throughout the day great complaints were made against the style of riding by the French Ladies, who blocked the track in such a way that the English ladies could not pass on the outer side. To pass on the inner side is against the law of racing, and this unfairness was so marked, that it evoked storms of hisses from the spectators, and those regulating the competition gave the French ladies repeated caution on the subject.”

Section two, with the French and English lady champions on its roster, started at 4:45 giving the first section a mere fifteen minutes to clear the track. Before long, Miss Lane came crashing down at the west wall and was left scrambling to get back on her bicycle. Twenty minutes into the race, Lisette and Miss Grace stood tied at 5 miles, 5 laps. Suddenly, Miss Grace fell badly forcing her off the track for most of the remainder of the race. By 5:45, only five racers remained in the race. In an unexpected turn of events, novice Harwood sprang into action and challenged Lisette in an attack. At 6:00, Lisette fell at the west end and, as The Star, 21 Nov 1895 reported, “Miss Harwood, who had been overhauling her in splendid style, spurted so well that, when Mdlle Lisette was once more on the track, Miss Harwood was three laps ahead.” Miss Grace returned to the track around this time, and was “loudly cheered” by her many fans in the audience. There was just enough time for one more accident before the race finished. At 6:30 Miss Lane crashed at the east end of the track, bruising her forehead and nose, and left the race. Harwood, shown leading the pack in the image above, finished the race in first place with 32 miles, 8 laps. Lisette was close behind in second with 32 miles, 5 laps. Crowd favourite Miss Grace completed a mere 14 miles, 7 laps leaving her out of contention for a prize. Last place went to Beany Voutro who finished a dismal 5 miles, 1 lap.

Section two, with the French and English lady champions on its roster, started at 4:45 giving the first section a mere fifteen minutes to clear the track. Before long, Miss Lane came crashing down at the west wall and was left scrambling to get back on her bicycle. Twenty minutes into the race, Lisette and Miss Grace stood tied at 5 miles, 5 laps. Suddenly, Miss Grace fell badly forcing her off the track for most of the remainder of the race. By 5:45, only five racers remained in the race. In an unexpected turn of events, novice Harwood sprang into action and challenged Lisette in an attack. At 6:00, Lisette fell at the west end and, as The Star, 21 Nov 1895 reported, “Miss Harwood, who had been overhauling her in splendid style, spurted so well that, when Mdlle Lisette was once more on the track, Miss Harwood was three laps ahead.” Miss Grace returned to the track around this time, and was “loudly cheered” by her many fans in the audience. There was just enough time for one more accident before the race finished. At 6:30 Miss Lane crashed at the east end of the track, bruising her forehead and nose, and left the race. Harwood, shown leading the pack in the image above, finished the race in first place with 32 miles, 8 laps. Lisette was close behind in second with 32 miles, 5 laps. Crowd favourite Miss Grace completed a mere 14 miles, 7 laps leaving her out of contention for a prize. Last place went to Beany Voutro who finished a dismal 5 miles, 1 lap.

Both sections had another run to complete before the day was done. The evening heats began at 7:08 pm and in consideration of the late start were abbreviated from 2 hours to 1.5 hours. Six riders started in section one, with a seventh, La Touch, joining half an hour later. There were no spills this time, and The Star reported “the whole rode exceedingly well, the spurting causing cheers as the English riders passed their French opponents, or the contrary.” (The Star, 21 Nov 1895) The second section, which started at 9:15 pm, proved much more exciting. Miss Grace, still smarting from her injury earlier in the day, and two other racers stood out, leaving seven in the field. The Star reported “This race resolved itself into a contest between Miss Harwood and Mdlle Lisette. These two ladies led the column at the start, and kept within three yards of each other throughout the hour and a half the race lasted, both riding with grace and finish. Mdlle Lisette had thrown off her sash for the race, while Miss Harwood – much the younger rider – wore the same dress as in the first race, black and gold, with white collarette.” The fastest lap was covered by Harwood in 3 minutes, 20 seconds. Harwood remained in first place when the race ended at 10:45pm, with 56 miles, 9 laps total, a narrow 3 laps lead ahead of Lisette and a strong advantage over Reillo who led the first section at 52 miles, 8 laps. Not a bad showing for Harwood, who was still an underdog at this early stage in her racing career.

Day One Aggregate Scores

Monica Harwood 56 miles, 9 laps

Lisette Marton 56 miles, 6 laps

Mdlle Reillo 52 miles, 8 laps

Mdlle Solange 52 miles, 7 laps

Marcelle Voutro 52 miles, 7 laps

Marie Cannoe 52 miles, 5 laps (may be an error for “Cannoc”)

Clare Gamble 51 miles, 9 laps

Rosa Blackburn 51 miles

Mdlle Eteogella 50 miles, 8 laps

Rosina Lane 49 miles, 3 laps

Lucie Latrielle 39 miles, 7 laps

Ellen Hutton 30 miles, 5 laps

Nellie La Touche 27 miles, 7 laps

Fanoche Voutro 22 miles, 9 laps

Clara Grace 14 miles, 7 laps

Miss Benham 8 miles (disqualified)

Beany Voutro unknown

Lilian Adaire unknown

Henrietta Palliarde unknown

Mdlle Aboukaia unknown

The second day of racing, Tuesday 19 November, played out much the same as the previous day leaving Harwood first, Marton second, and Marcelle Voutro third.The Daily News reported that “The best performances were those of Miss Harwood and Mdlle Lisette Marton, each of whom completed 100 miles in 6h 13m, Miss Harwood leading Lisette by a couple of yards,” adding that the “stage of this competition was productive of several exciting incidents. Some riders came again into grief, and there was something more than a suspicion that the falls of at least one of the riders (Miss Blackburn) was due to anything but an accident.” This accusation arose from suspicious behaviour during section two’s first run. The Star described the race as starting at 1:13 following a caution to the French riders. Solange went up front, setting a good pace with her fellow French riders on her tail and the two English riders at the back of the pack. “Before three miles had been covered,” the paper reported, “Miss Blackburn had ridden into third position with Miss Gamble in close attendance. When seven miles had been completed Miss Blackburn forced her way to the front, the leaders having now lapped the stragglers. A mile later Miss Blackburn fell, and lost several miles.” The umpire agreed that the fall was caused deliberately. Solange and Reillo were disqualified for the remainder of the run for fouling Blackburn. The two aggrieved English riders recovered and ended the race first and second in their section, fourth and fifth in the aggregate scores.

By Day Three, only 16 riders remained in the race. Harwood retained first place, with 190 miles, 2 laps, a slight but comfortable lead over Lisette who was one lap shy of 3 miles behind her. There was another great crash for Blackburn and Reillo, and Cannoe fell badly. Grace was now in third last place with no hope of catching up to the respectable standing expected of her as reigning English champion. On Day Four, The Daily News, 22 Nov 1895 noted that the stands were packed with spectators, while on the track, “The riding was once more interspersed with accidental spills,” in one of which left Blackburn “so severely shaken that she was away nearly half an hour.” Harwood and Lisette retained the top two places.

Day Five attracted the largest audience yet. Clearly, word was spreading that the ladies races were a attraction, no doubt something tabloid style reporting contributed to. The Daily Star named Cannoe as the star rider of the day for fighting her way to the lead of Section One and a good place overall in the aggregate scores. The story also commented that, “fouling was once more prominent on the part of the French competitors.” The main culprits were Eteogella and Marcelle, and their victim was, who lost lap on account of their aggressive riding. Grace also fell and left the track. Undoubtedly, national loyalty motivated the French riders to interfere with the best English riders to the benefit of their own champion Lisette. The last lap was an exciting one, with Harwood and Lisette locked in at a tremendous pace, covering one lap in under 20 seconds. Despite these tactics, Harwood retained in the lead with 309 miles, 4 laps while Lisette stayed in second place with 306 miles, 7 laps.

Saturday 23 November marked the conclusion of the race. It was Day Six, and The Royal Aquarium was packed. Demand for seats was so high that tickets sold for a guinea for the best view and a half-a-guinea for general admission. Lloyds Weekly News analysed the phenomenon, writing “The contest, which is the first of its kind held in England, proved of a decidedly popular character, and so large were the crowds that flocked to it each evening that the managers of the building greatly increased the price of admission to the reserved portion of the building.” A good play by play of the action, which picked up in the final laps of the race and features national strategies, comes from Western Mail, which explained “In the second lap Mrs Grace, who had but 301 miles recorded, took premier position, and it at once became apparent that her task was to pace her countrywoman.” Lisette tailed Harwood closely, “literally hanging from the wheel of her only opponent.” The report continued, “Lisette had been making efforts to take the lead, and the speed became tremendous, at one time exceeding eighteen miles an hour. Finding her exertions inoperative, Lisette called in strategy to her aid. Easing the pace for a few minutes, she bided her chance, and then, suddenly, at five minutes past ten, amidst great excitement, she suddenly shot ahead. Harwood tried all she knew to regain the forfeited position. Mdlle Lisette was 26 laps behind Harwood, and her plan was evidently to tire down the English rider. The plucky French lady desperately exerted every nerve to pick up her laps, but Miss Harwood rode wisely, keeping her strength and stamina well in hand.”

Saturday 23 November marked the conclusion of the race. It was Day Six, and The Royal Aquarium was packed. Demand for seats was so high that tickets sold for a guinea for the best view and a half-a-guinea for general admission. Lloyds Weekly News analysed the phenomenon, writing “The contest, which is the first of its kind held in England, proved of a decidedly popular character, and so large were the crowds that flocked to it each evening that the managers of the building greatly increased the price of admission to the reserved portion of the building.” A good play by play of the action, which picked up in the final laps of the race and features national strategies, comes from Western Mail, which explained “In the second lap Mrs Grace, who had but 301 miles recorded, took premier position, and it at once became apparent that her task was to pace her countrywoman.” Lisette tailed Harwood closely, “literally hanging from the wheel of her only opponent.” The report continued, “Lisette had been making efforts to take the lead, and the speed became tremendous, at one time exceeding eighteen miles an hour. Finding her exertions inoperative, Lisette called in strategy to her aid. Easing the pace for a few minutes, she bided her chance, and then, suddenly, at five minutes past ten, amidst great excitement, she suddenly shot ahead. Harwood tried all she knew to regain the forfeited position. Mdlle Lisette was 26 laps behind Harwood, and her plan was evidently to tire down the English rider. The plucky French lady desperately exerted every nerve to pick up her laps, but Miss Harwood rode wisely, keeping her strength and stamina well in hand.”

At twenty to eleven that night, Harwood was declared the winner for completing 371 miles, 21 laps. Lisette placed second at 368 miles, 5 laps. Cannoe from the first section came in third in the aggregate scores with 355 miles, 8 laps. Monetary prizes were awarded for the top places. Though the rates are not clear for the 1885 race, a subsequent six day race at The Royal Aquarium awarded £50 for first place, £30 for second, £20 for third, £5 for fourth, and four other prizes for leading riders. First prize was the equivalent of about £1200 if converted to 2015 terms, a good pay out for a week’s racing and an amount in excess of what many male cyclists could expect for similar achievements.

The Six Day Race was just the opening event of the ladies’ twelve days cycle races at The Royal Aquarium, and one of many races on the circuit at the end of 1895.The remaining days saw a variety of novel races, starting with “A Great Race” in which women packed the track all at once for one continuous race from 2:00-10:30 pm. A second six day race was held, finishing December 4th, though it did not prove as popular as the first one. Some familiar names appear in the winning line up. French racer Mdlle Cannoe won, followed by Miss Grace. Harwood also participated, but suffered a bad spill that pur her out of the running for a prize, so she paced Miss Grace instead as part of their competative strategy. A few racers from The Royal Aquarium track competed in an Five Day Race at Bingley Hall, Birmingham December 16-21st, which Grace won, earning back her good name after a poor showing in London. (This was intended to be a six day race, but was abbreviated due to a late start.) Back at The Royal Aquarium, an Eleven Day Ladies’ Cycle Race ran December 18-28th. French riders took all the top places, with Mdlle Palliarde winning with 644 miles, 3 laps and Mdlle Marcelle Vautro second at 644 miles, 2 laps. England’s Miss Field and Miss Hutton places fourth and fifth respectively. Champions Harwood, Lisette and Grace did not participate in the eleven day race, and the winners circle was different from the first six day race held at the same venue. This may suggest that racers specialized in soecific events and that the unpredictability of the track could make or break racers’ chances.

Gender Politics on The Track

In addition to being a new outlet for women’s cycling as sport and entertainment, another consideration that makes the races at The Royal Aquarium of historical interest is the extent to which they embodied late Victorian gender politics. Voyeurism and the male gaze were inescapable features of the spectacle of women’s cycling, whether racing or at leisure, in the late nineteenth century. The Royal Aquarium put female racers wearing form revealing costumes and breeches, performing a level of physical activity not seen among women in everyday life, and sitting astride diamond frame bicycles which in itself was still considered risqué on view for an audience of men more than willing to pay for a glimpse of them. The small velodrome track offered a more intimate perspective of the racers that road races did. Lady cyclists rode round and round in close proximity to the crowd, giving men a close and continuous view of them. Arthur Munby, a prolific diarist known for his fetishistic portrayals of women in scenarios such as wearing breeches, went to see the French lady cyclists performing at the Royal Pleasure Gardens, North Woolwich in 1869. He described the scene excitedly, writing,

In addition to being a new outlet for women’s cycling as sport and entertainment, another consideration that makes the races at The Royal Aquarium of historical interest is the extent to which they embodied late Victorian gender politics. Voyeurism and the male gaze were inescapable features of the spectacle of women’s cycling, whether racing or at leisure, in the late nineteenth century. The Royal Aquarium put female racers wearing form revealing costumes and breeches, performing a level of physical activity not seen among women in everyday life, and sitting astride diamond frame bicycles which in itself was still considered risqué on view for an audience of men more than willing to pay for a glimpse of them. The small velodrome track offered a more intimate perspective of the racers that road races did. Lady cyclists rode round and round in close proximity to the crowd, giving men a close and continuous view of them. Arthur Munby, a prolific diarist known for his fetishistic portrayals of women in scenarios such as wearing breeches, went to see the French lady cyclists performing at the Royal Pleasure Gardens, North Woolwich in 1869. He described the scene excitedly, writing,

“They were drest [sic] as men; in jockey caps, and satin jackets and short breeches ending above the knee, and long stockings, and mid length boots. Thus clad, they stepped unabashed into the midst, and mounting their ‘bicycles’; each girl throwing her leg over and sitting astride on the saddle. And they started, amidst cheers; pursuing one another round and round the hall, curving in and out, sometimes rising in their stirrups (so to speak) as if trotting, sometimes throwing one or both legs up whilst at full speed.” (Diary of Arthur Munby, 1869)

Though Munby approved of women in breeches, there is no doubt of the sexual innuendo in his description of scantily dressed lady cyclists riding astride, their breech-clad legs undulating up and down as they raced around the track at delirious speed. The relationship between female cyclist and male spectator at The Royal Aquarium races resembles the dynamics of parasexuality described by Peter Bailey in his article “Parasexuality and Glamour: The Victorian barmaid as cultural prototype,” which explores the male gaze and women on view in the case of the Victorian barmaid and other similar scenarios.

National identity also influenced the dynamics of fandom at the ladies’s cycle races. Press and promotions for the ladies cycle races at The Royal Aquarium positioned the event as an international contest, and played up historic rivalries between countries. Head to head battles between French and English champions roused excitement in the stands. Reflecting on the political resonance of the races, Lloyds Weekly News (22 Nov 1895) acknowledged national loyalties, noting “The fact that the struggle for first was between an English and a French lady naturally enhanced the interest in the contest, and when from time to time the two leaders spurted and rode a few laps at a fast pace the excitement and cheering became so great as to drown the music of the band.”

The danger implicit in women’s track racing was another compelling feature for audience members and a news hook for the press. Nearly every report on the races mention falls, smashes, collisions, and women sent off the track. Bicycle News speculated that “probably three-fourths of the audience at The Royal Aquarium ‘ladies cycle races’ attend in the hopes of seeing what one man, the other day, termed ‘a holy smash.'” (“Interesting Bits of Information,” The Hub, 1897) While danger was part of the appeal of watching racing, it was also one of the main grounds for criticizing women’s races. Objections were raised to women’s cycle racing on the grounds that it was too risky, taxing on the health of riders, and exposed them to unnecessary hazards. Injury was a given, and death a possibility. The Queen’s described an 1895 accident that reinforced the magazine’s misgivings about racing commenting, “The wholesale smash which we feared would occur on the Aquarium track has come about. Last Saturday some half-dozen of the riders fell in a heap, including the unfortunate Miss Blackburn, who has been so unfortunate all the time. Mlle. Reilly, one of the best of the French continent was stunned, and had to be removed to the hospital.” A minor crash is shown in the inset of The Penny Illustrated image of Lisette winning an 1896 race at The Royal Aquarium shown right. In a much worse accident, English cyclist Dottie Farnsworth died due to injuries sustained in a fall while racing in New York in 1902.

The danger implicit in women’s track racing was another compelling feature for audience members and a news hook for the press. Nearly every report on the races mention falls, smashes, collisions, and women sent off the track. Bicycle News speculated that “probably three-fourths of the audience at The Royal Aquarium ‘ladies cycle races’ attend in the hopes of seeing what one man, the other day, termed ‘a holy smash.'” (“Interesting Bits of Information,” The Hub, 1897) While danger was part of the appeal of watching racing, it was also one of the main grounds for criticizing women’s races. Objections were raised to women’s cycle racing on the grounds that it was too risky, taxing on the health of riders, and exposed them to unnecessary hazards. Injury was a given, and death a possibility. The Queen’s described an 1895 accident that reinforced the magazine’s misgivings about racing commenting, “The wholesale smash which we feared would occur on the Aquarium track has come about. Last Saturday some half-dozen of the riders fell in a heap, including the unfortunate Miss Blackburn, who has been so unfortunate all the time. Mlle. Reilly, one of the best of the French continent was stunned, and had to be removed to the hospital.” A minor crash is shown in the inset of The Penny Illustrated image of Lisette winning an 1896 race at The Royal Aquarium shown right. In a much worse accident, English cyclist Dottie Farnsworth died due to injuries sustained in a fall while racing in New York in 1902.

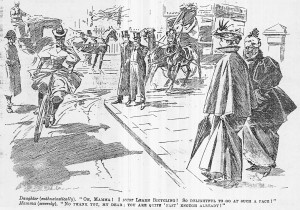

Late-nineteenth century gender politics and constructs of respectable womanhood were ubiquitous, even for the most liberated lady cyclists, and their influence is readily apparent in both the practice and perception of women’s cycle racing riding. Participating in physically demanding, competitive activities was deemed unwomanly by wider society, and lady cyclists were shunned for trespassing in sport, which was considered a male preserve. The racers themselves were criticized as lacking in feminine virtue, such as one racer who was called a unsuitable for motherhood on account of her aggression on the track by a magazine. Public reception to the races was mixed. The most vocal social commentators in the press adopted a critical stance, while others approached it as harmless entertainment. The Queen observed that, “The various criticisms upon the matter have been most amusing. The cycling press has almost unanimously expressed strong disapproval, and in one or two cases the writers have been almost hysterical in their expressions of disgust. Other sections of the press, however, have taken a more reasonable and tolerant view, and see nothing worse in it than dancing and other performances by women on the stage.”

An association with women of the stage was a mixed blessing. Female actresses and performers suffered frequent questions about their character and respectability in the form of accusations of prostitution. The public consciousness of the late-Victorian era associated lady cycle racers and performers with female gymnasts and circus acts. This put them in a category somewhere on the spectrum of late Victorian prostitution in the public eye. Like gymnasts, cycle racers wore scant costumes, such as breeches, tights and bodices or short skirts that inevitably flew about in leg revealing ways, and performed with a level of physicality though unbecoming of respectable women in this time. This association with vice was compounded for female cyclists who performed at The Royal Aquarium, a place reputed to be the haunt of prostitutes and the men who availed themselves of their services.

One camp of people who supported women’s racing in principle were those associated with women’s equality, cycle clubs and dress reform–especially those with overlapping interests in all three. In her work on the history of women’s cycle racing, Clare Simpson identifies the Chelsea Rationalists as a progressive women’s cycling club that believed women had the right to race. The club held their own races and offered awards to encourage women to participate. Monica Harwood, winner of the 1895 Ladies’ Six Day Race at The Royal Aquarium, served as their captain. (Clare Simpson, Cycling and Society,) Another organisation that defended women’s racing was the MHCA, a cycling co-op founded to promote cycling for working women. The MHCA backed ladies’ cycle races on the principle that women had a right to earn a livelihood as professional racers. The organisation passed a resolution declaring that, “The MHCA, although composed solely of women who cycle for pleasure and convenience, deprecate any attempt to close the career of professional cyclist to those women who may wish to cycle for profit. The MHCA expresses no opinion as to whether or not such a career is desirable for women, but it claims for all women the right and liberty to decide this question for themselves. Therefore the MHCA appeals to the NCU to frame such rules as are necessary to secure for women all the advantages which legislation can secure for cyclists.”

Women’s cycle racing had a serious sporting and income generating side, which is often overlooked. Many of the ladies who rode at The Royal Aquarium and in other races were professional athletes. They trained for races, had coaches and managers, and often worked closely with male racers who helped pace and prepare them for competition. Harwood’s first racing tutor was Clare Grace, an accomplished racer several years her senior who’s title as English champion she would eventually take. In an 1896 interview with The Hub Harwood, who by then had a male coach, described her training regime, explaining “Well, my trainer who is himself an old time ‘pro.’ and a record holder, is somewhat strict, and I need scarcely assume you that he spares no pains to render me fit and well for the track when I have a severe contest in view…I adopt rational and regular habits, and, in addition, I go daily in for four or five hours’ riding, together with considerable walking exercise, and practice with the dumb-bells.” Some riders had lucrative sponsorship deals. The Simpson Lever Chain Co sponsored Lisette in 1896. Harwood mentioned her Élysées machine and Dunlop tyres in her interview with The Hub, endorsements that were likely paid product placements. Venues hosting ladies cycle races sold tickets in the hundreds and even thousands at the height of interest, making it a good business venture. This translated to excellent exposure for advertisers who sponsored races and racers. There was money to be made by racers and their teams in the forms of prizes, which could amount to over £100 per week for racers in their prime. Lisette, for example, won £60 for first place at The Royal Aquarium in 1896. Riders were also awarded trophies, new bicycles, medals, and jewelry. Top racers like Harwood and Lisette were treated like celebrities, interviewed by magazines such as The Hub, and photographed in race portraits such as the Jules Beau image of Lisette shown right. Women’s racing was a profitable enterprise for the competitors, venues, and cycle companies involved–possibly even more so than the men’s cycle racing industry dating to the same era.

Women’s cycle racing had a serious sporting and income generating side, which is often overlooked. Many of the ladies who rode at The Royal Aquarium and in other races were professional athletes. They trained for races, had coaches and managers, and often worked closely with male racers who helped pace and prepare them for competition. Harwood’s first racing tutor was Clare Grace, an accomplished racer several years her senior who’s title as English champion she would eventually take. In an 1896 interview with The Hub Harwood, who by then had a male coach, described her training regime, explaining “Well, my trainer who is himself an old time ‘pro.’ and a record holder, is somewhat strict, and I need scarcely assume you that he spares no pains to render me fit and well for the track when I have a severe contest in view…I adopt rational and regular habits, and, in addition, I go daily in for four or five hours’ riding, together with considerable walking exercise, and practice with the dumb-bells.” Some riders had lucrative sponsorship deals. The Simpson Lever Chain Co sponsored Lisette in 1896. Harwood mentioned her Élysées machine and Dunlop tyres in her interview with The Hub, endorsements that were likely paid product placements. Venues hosting ladies cycle races sold tickets in the hundreds and even thousands at the height of interest, making it a good business venture. This translated to excellent exposure for advertisers who sponsored races and racers. There was money to be made by racers and their teams in the forms of prizes, which could amount to over £100 per week for racers in their prime. Lisette, for example, won £60 for first place at The Royal Aquarium in 1896. Riders were also awarded trophies, new bicycles, medals, and jewelry. Top racers like Harwood and Lisette were treated like celebrities, interviewed by magazines such as The Hub, and photographed in race portraits such as the Jules Beau image of Lisette shown right. Women’s racing was a profitable enterprise for the competitors, venues, and cycle companies involved–possibly even more so than the men’s cycle racing industry dating to the same era.

Interviews and profiles of women cycle racers give us some insight into what racing meant to them on a more personal level. Harwood identified the 1895 Six day race at The Royal Aquarium as particularly memorable in an interview for The Hub conducted a year after her win. When asked what she considered her best performance, Harwood, who had been modest about her accomplishments up to that point in the interview, welled up with pride. “Her eyes scintillated with joy,” the interviewer observed, “and for a moment there was an evident struggle in her mind between her natural reserve and a pardonable inclination to give vent to what, in spite of herself, she could not but look upon as a very meritorious performance. Then she replied, smiling:–‘Oh, that was when I beat Lissette (sic), last year. I do not think any future victory will ever efface the recollection of that event from my mind.” Her 1895 victory at The Royal Aquarium brought her fame and prizes as an international cycling champion, but when the dust settled it was her personal triumph that she treasured, a reminder of the individual accomplishments and character of the remarkable women racers who took to the late Victorian cycle track.

Conclusion

Sport and spectacle collided on the track during the ladies’ cycle races at The Royal Aquarium. Women’s cycle races remained a popular annual event at The Royal Aquarium until 1898, after which they were only occasionally held and were largely ignored by the press. A 1901 race only attracted English riders, and though three of them were England’s greatest cycle racers–Rosa Blackburn, Monica Harwood, and Mrs Anderson–ticket sales were disappointing. Cycling sport and leisure entered a lull around the turn of the century and ladies’s six day races fell out of fashion. The Royal Aquarium continued its spiral into decline and closed to the public not long after, only to be sold off and demolished in 1903. Though the fad for women’s cycling was short-lived, the races held at The Royal Aquarium from 1895-1901 marked a brief but important episode in the development of women’s bicycle racing as both sport and spectacle in late Victorian culture.

Selected Sources

“The English Champion Lady Champion: A Chat with Miss Harwood,” The Hub, 1896.

“Interesting Bits of Information,” The Hub, 1897.

The Queen, various Nov-Dec 1895.

Arthur Munby, Diary, 21 June 1869

Newspapers dating Nov-Dec 1895, including The Times, The Star, Lloyds Weekly News, The Standard, and The Daily News.

Bailey, Peter. “Parasexuality and Glamour: The Victorian barmaid as cultural prototype,” Gender and History (June 1990) vol 2, pp 148-273.

Simpson, Clare. “Capitalising on Curiosity: Women’s Professional Cycle Racing in the Nineteenth Century,” in Dave Horton, Paul Rosen and Peter Cox ed, Cycling and Society (Ashgate, 3007) pp 47-66.

Newspaper clippings and further details about Six Day Races available at http://www.sixday.org.uk

Title Image: S Begg, artists rendition of the ladies’ races at The Royal Aquarium, 1896.

Do you have all the names of the riders in the photograph from The Queen? I can identify a few (Nellie Hutton upper right…). All photos of female racers are wellcome and I can send you some in return.

Regards,

Dag Hammar

(Cykelhistoriska Föreningen, Sweden)