**Updated: Originally posted 12 May 2015.

In 1893, a remarkable sixteen year old girl rode from Brighton to London and back in record time, covering the full distance in just over 8.5 hours. Her name was Tessie Reynolds, and though the news of the day had much to say about her ride and the outfit she accomplished it in, she is one of Britain’s unsung sporting heroes.

Tessie was born in Newport on the Isle of Wight on August 20th 1877. Her family soon relocated to Kemp Town, a working class neighbourhood in the seaside town of Brighton, in 1877. She was the oldest of eleven children. Her father RJ Reynolds had a number of connections to the cycling world. He ran a bicycle dealer with a shop at 25 Brighton Road, was a member of the National Cycle Union, served as secretary to a local cycling club, and umpired bicycle races. To make ends meet he dabbled in a number of professions including PE instructor for the Brighton Police, coaching local athletes and a serving a stint in the army. Tessie’s mother managed the family’s boarding house, which was popular with cycle tourists.

Under their father’s tutelage, the Reynolds children learned to cycle, fence, box, and practice sports of all kinds. Tessie in particular set her heart on competitive cycling. Preston Park Velodrome, a state of the art racing track was built in 1877, the same year that Tessie was born, was three miles from the Reynolds’ house. Her father may have been able to negotiate use of Preston Park Velodrome for Tessie’s training regime, a rarity at a time when racing was seen as a mens sport. The London to Brighton cycle route was popular with leisure riders and athletes in the late Victorian era, placing Tessie even more in the centre of cycling culture. Tessie’s family connections to the cycling world, her proximity to both a velodrome and a key route for setting road records, and her determination culminated in a remarkable accomplishment for this young athlete.

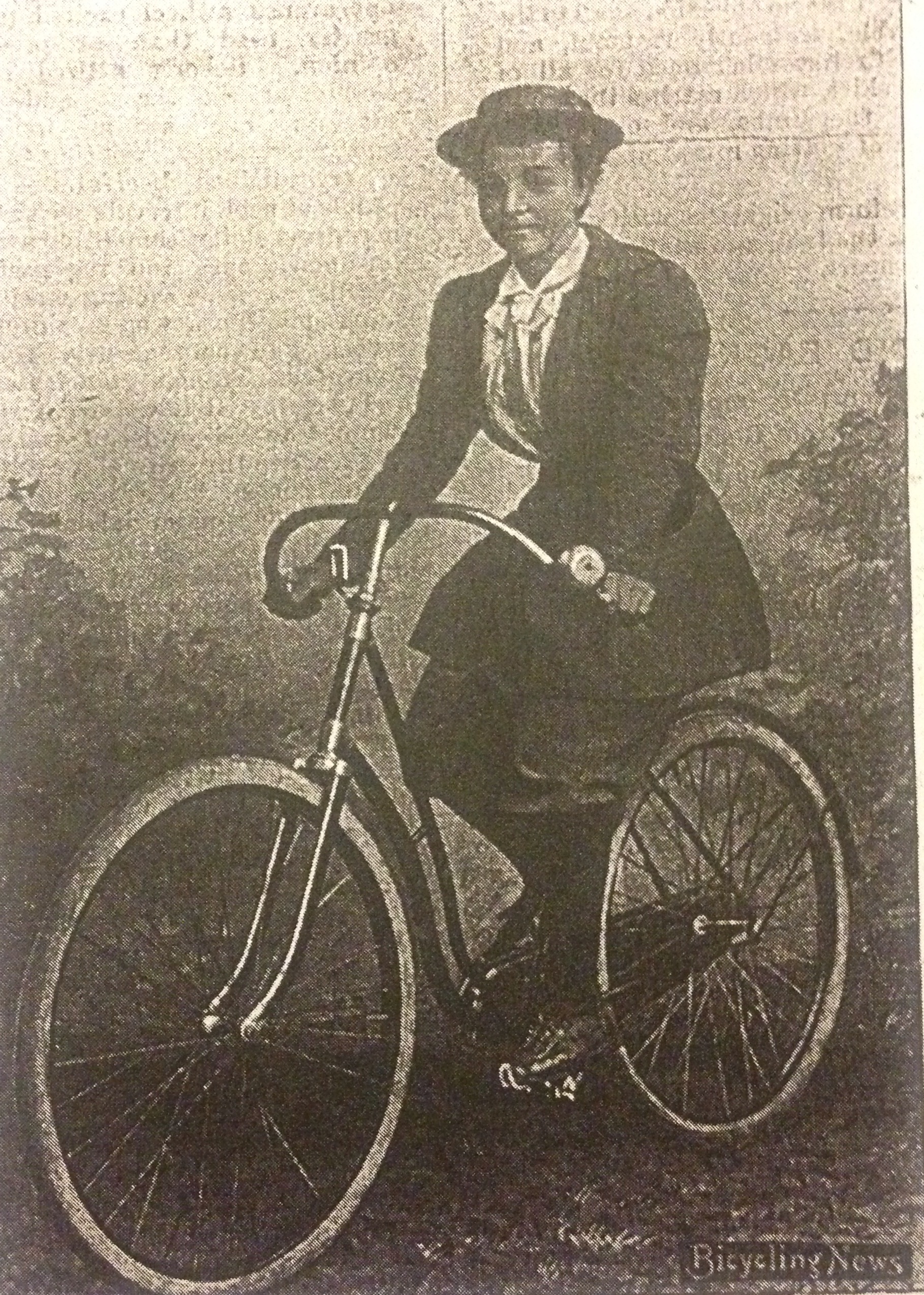

The image of Tessie shown above, taken in 1890 three years before her record breaking ride, depicts her on a bicycle made by RS Lovelace, a manufacturer from Henstridge. By that time, she had already adopted rational wear and is poised as you can see, a diamond frame with an upper crossbar and downward curved handle bar. This machine is readily identifiable as a racing bike. It differed distinctly from a standard ladies’ bicycle, which in the 1890s would have been a drop frame safety with upright handle bars and an overall geometry that made the rider sit upright, Tessie’s machine, outfit, and stance are a stark contrast with the the image is “A Typical Lady Cyclist,” shown below, who wears a long riding habit and rides a drop frame as prescribed for women during the 1890s.

Tessie’s record setting ride from Brighton to London and back landed her briefly in the national cycling press. According to Bicycling News, Tessie set out from the Brighton Aquarium at 5:00am on the morning of September 10th, 1893. She rode a Premium safety geared to 56, scaling under 80lbs. She reached Hyde Park at 9:13am without stopping en route. On the way back, she made three stoppages at Smitham Bottom, Crawley, and Hickstead. By 1:38pm, she had returned to her starting point at the Brighton Aquarium. Tessie had completed the ride in a record setting 8 hours, 38 minutes including stops, covering 120 miles at an average speed of twelve miles per hour. While impressive, Bicycling News commented that her “plucky performance on the road proved loss of surprise to those who knew her exceptional powers awheel than to the general public.”

Tessie’s record setting ride from Brighton to London and back landed her briefly in the national cycling press. According to Bicycling News, Tessie set out from the Brighton Aquarium at 5:00am on the morning of September 10th, 1893. She rode a Premium safety geared to 56, scaling under 80lbs. She reached Hyde Park at 9:13am without stopping en route. On the way back, she made three stoppages at Smitham Bottom, Crawley, and Hickstead. By 1:38pm, she had returned to her starting point at the Brighton Aquarium. Tessie had completed the ride in a record setting 8 hours, 38 minutes including stops, covering 120 miles at an average speed of twelve miles per hour. While impressive, Bicycling News commented that her “plucky performance on the road proved loss of surprise to those who knew her exceptional powers awheel than to the general public.”

The Brighton to London and back route that Tessie tested her cycling ability on was a popular choice for record setting. In 1890, FW Sherland set a record on the route of 9 hours, 19 minutes. The same month that Tessie set her record, SF Edge broke the men’s record with a time of 6 hours 57 minutes 30 seconds. Both male cyclists had their attempts at the record formally adjudicated and their times were entered into the official record book of their club and the cycling union. Tessie’s ride was timed by an umpire and followed all racing conventions. She was accompanied by three male pacemakers along the way. Tessie’s record, however, was regarded as novelty and was not be formally acknowledged by a racing body since as a woman her time was not admissible.

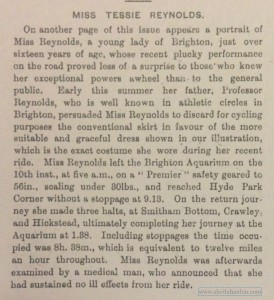

Tessie’s road ride was an extraordinary feat in an age where women’s athleticism was discouraged and moderation was prescribed for any physical activity undertaken. Women’s cycle racing was not endorsed in popular opinion, nor was it sanctioned by racing organisations. If you look closely at the news clipping shown right, you will note that in the last line Bicycling News felt the need to reassure readers that Tessie’s record setting ride had no physical side-effects confirming that “Miss Reynolds was afterwards examined by a medical man, who announced that she had sustained no ill effects from her ride.” Despite Tessie’s athletic prows, the potential hazard racing posed to her health was a serious concern for doctors and a public in an age where overexertion was thought to cause medical disorders in women. As you’ll recall from an earlier blog post on The Ladies Races at the Aquarium, women racers were thought to risk heart disease, pneumatic disorders, overdeveloped muscles, nervous disorders, and even infertility. Well known cycling specialist and medical expert Dr JB Turner, a regular contributor to scientific journals such as The Lancet, even went so far as to say that women should not be allowed to race because the risk to their health was too great.

Tessie’s road ride was an extraordinary feat in an age where women’s athleticism was discouraged and moderation was prescribed for any physical activity undertaken. Women’s cycle racing was not endorsed in popular opinion, nor was it sanctioned by racing organisations. If you look closely at the news clipping shown right, you will note that in the last line Bicycling News felt the need to reassure readers that Tessie’s record setting ride had no physical side-effects confirming that “Miss Reynolds was afterwards examined by a medical man, who announced that she had sustained no ill effects from her ride.” Despite Tessie’s athletic prows, the potential hazard racing posed to her health was a serious concern for doctors and a public in an age where overexertion was thought to cause medical disorders in women. As you’ll recall from an earlier blog post on The Ladies Races at the Aquarium, women racers were thought to risk heart disease, pneumatic disorders, overdeveloped muscles, nervous disorders, and even infertility. Well known cycling specialist and medical expert Dr JB Turner, a regular contributor to scientific journals such as The Lancet, even went so far as to say that women should not be allowed to race because the risk to their health was too great.

Tessie’s ride was unusual. But, as a late Victorian era female cycle racer and record setter she was in good company. Other pioneering women cyclists set records in and around Tessie’s 1893 ride. Ina Mason of Liverpool, for example, secured long distance records in the early 1890s. Bicycling News for 19 August 1893 reported that she “accomplished an excellent ride last Thursday, when, in company of a well-known Liverpool rider of the same sex, she rode from Birkenhead to Llangollen (North Wales) and back–a journey of over eighty miles–in seven hours and a quarter.” The pair took a long halt along the way at Wrexham for dinner after four hours riding, and had a short stop in Sutton on the return journey. Not long after Tessie’s moment of fame, American amateur rider Annie “Londonderry” Cohen Kopchovsky (1870-1947) came to attention for her 1894-5 attempt to cycle around the world. there were also the many belles of the indoor racing track such English sweetheart Miss Hardwood and French champion Lisette.

The outfit Tessie wore on her record breaking ride received nearly as much attention as her athletic achievement. Tessie famously wore a rational knickerbocker costume consisting of a long jacket over knee length breeches, as shown in the Bicycling News portrait shown left. Tessie preferred to ride in a rational cycling costume both out of practicality and as a commitment to dress reform. Her sisters helped tailor the outfit that she wore as part of the tight-knit family’s support for her attempt on the record. Rationals were a controversial costume that defied 1890s conventions dictating that women wear long skirts or dresses. The public nature of Tessie’ ride across country roads, through towns along the way, and directly into central London and Brighton made the display of the female body even more visible.

The outfit Tessie wore on her record breaking ride received nearly as much attention as her athletic achievement. Tessie famously wore a rational knickerbocker costume consisting of a long jacket over knee length breeches, as shown in the Bicycling News portrait shown left. Tessie preferred to ride in a rational cycling costume both out of practicality and as a commitment to dress reform. Her sisters helped tailor the outfit that she wore as part of the tight-knit family’s support for her attempt on the record. Rationals were a controversial costume that defied 1890s conventions dictating that women wear long skirts or dresses. The public nature of Tessie’ ride across country roads, through towns along the way, and directly into central London and Brighton made the display of the female body even more visible.

Rational dress was, without a doubt, more suitable for cycling than skirts and dresses. This was especially true for racing and time trials which would have been hampered by riding in conventional women’s dress. Bicycling News revealed that Tessie’s father approved of rational cycling costumes. “Early this summer,” the magazine reported, “her father, Professor Reynolds, who is well known in athletic circles in Brighton, persuaded Miss Reynolds to discard for cycling purposes the conventional skirt in favour of the more suitable and graceful dress shown in our illustration, which is the exact costume she wore during her recent ride.”

On the subject of dress, Tessie wrote a letter to the ladies page of Bicycling News, edited by Violet Lorne of the Ladies Cycling Association, describing her costume and confirming her commitment to dress reform. In a letter printed 30 September 1893, she explained, “You have no doubt heard of my riding in knickerbockers. I should like to know your opinion on this costume for ladies. I find mine very comfortable and convenient.” Though she did not recommend rationals as everyday wear for women who used bicycles for shopping trips or commuting to work, she did endorse it for touring or athletic riding. In response to the many requests she received for pattern for her outfit, including one from a woman who suffered a spill on account of her skirt that left her unconscious for twenty minutes, she revealed, “I have not a pattern for it as I cut it out and made it entirely from my idea of what was wanted,” adding that she had tried on several ready made designs but none had been to her satisfaction. Violet Lorne closed her article with praise for Tessie’s bold new costume, stating, “I think Miss Reynold’s costume is undoubtedly the cycling costume of the future, and I feel sure feminine cycling will reach, with its general adoption, to heights which are at present impossible for it. I congratulate Miss Reynolds on her courage in being an apostate of the movement.”

Leading cycling expert G. Lacy Hillier championed Tessie’s athletic accomplishments and her contribution to the rational dress movement, noting his pleasure at seeing positive press for her record setting ride. Hillier’s article entitled “Rational Dress For Ladies” in the 30 September 1893 edition of Bicycling News, opened with the statement:

“Of all the curious development which it has ever been my lot to come across, commend me to the attitude of the Lady’s Pictorial towards Miss Reynolds, who, in a costume closely approximating to that of a male person, rode from London to Brighton and back in remarkably good time. Plenty of varying opinions have been expressed concerning the ride of this young lady of 16, but that the Lady’s Pictorial–some of the correspondents of which are always shrieking for the legislative elimination of the cyclist–should not only publish Miss Reynold’s portrait, but actually give her performance a commendatory notice, is so amazing that I am daily looking out for blue rain. Miss Reynold’s, I am well assured, is but the forerunner of a big movement–the stormy petrel heralding the storm of revolt against the petticoat.”

Hillier’s article continued in defence of both cycling and rational dress for women. He looked back to earlier in his career when he was asked to adjudicate an exhibit of “the most irrational ‘Rational’ dresses” at which he told his co-adjudicators that women’s dress would only be reformed when there was a practical need for it, not merely a fad. Bloomers, he felt, where unnecessary so long as women abstained from athletics, pointing as an example to his imagined “The Lady Flabella” avoiding all exertion and reclining on her sofa suffering nerves and dyspepsia as she wafted smelling salts. In the intervening years, however, had arrived vogues for archery, croquet, lawn tennis and cycling which necessitated women’s clothing that was suitable for sport and recreation.

First the tricycle, and later the safety bicycle made cycling accessible for women, though Mrs Grundy reared her head time and time again to denounce riding by those of a feminine persuasion. By the 1890s, more and more women were riding for pleasure and some like Tessie were setting records, but women’s models remained inferior to men’s models and dress constraints endured. Hillier summarised the limits on women’s cycling writing “The safety bicycle, as made for ladies’ use is but a compromise; it is a good machine–considering. The lady rider does her best; it is excellent considering. The costume of the lady rider has been, by experience, so far perfected that it is as pleasing and graceful as it possibly can be–considering.” Cycling for women was in his estimation far from perfect, all things considered.

Using Tessie as an example, he continued “A well-known cycling legislator recently remarked that he would like to set some of Miss Reynolds’s critics the task of riding from Brighton to London and back with a skirt on.” He also pointed out the lack of objection to men’s fashions with a feminine feel, such as hunting garb, gymnastic blouses, and voluminous bathing outfits as evidence that society could survive the blurring of gender lines in clothing. “Why,” he asks, “should the weaker sex be handicapped with the skirt–it is a terrible handicap,” pointing out that it is not only cumbersome but dangerous in the case of cycling. “The woman who went bathing in a ball gown, or hunting in a tea gown, would be deemed an imbecile,” Hillier added, noting that specialised costumes were accepted in other sports making objections to rational cycling costumes unjustifiable. France was already ahead of England in this regard, as illustrated in the painting of the lady cyclists lounging in rational cycling costumes in Paris’s Bois de Bolougne shown above. Rational costumes were en vogue and “French lady riders are to-day using ordinary safety bicycles with the straight top stay,” thus solving two problems in one fell swoop, firstly dress since rationals were accepted and secondly eliminating the practice of weakening the structure of a women’s bicycle by removing the cross bar to accommodate skirts.

Using Tessie as an example, he continued “A well-known cycling legislator recently remarked that he would like to set some of Miss Reynolds’s critics the task of riding from Brighton to London and back with a skirt on.” He also pointed out the lack of objection to men’s fashions with a feminine feel, such as hunting garb, gymnastic blouses, and voluminous bathing outfits as evidence that society could survive the blurring of gender lines in clothing. “Why,” he asks, “should the weaker sex be handicapped with the skirt–it is a terrible handicap,” pointing out that it is not only cumbersome but dangerous in the case of cycling. “The woman who went bathing in a ball gown, or hunting in a tea gown, would be deemed an imbecile,” Hillier added, noting that specialised costumes were accepted in other sports making objections to rational cycling costumes unjustifiable. France was already ahead of England in this regard, as illustrated in the painting of the lady cyclists lounging in rational cycling costumes in Paris’s Bois de Bolougne shown above. Rational costumes were en vogue and “French lady riders are to-day using ordinary safety bicycles with the straight top stay,” thus solving two problems in one fell swoop, firstly dress since rationals were accepted and secondly eliminating the practice of weakening the structure of a women’s bicycle by removing the cross bar to accommodate skirts.

Returning to Tessie, Hillier concluded that by continuing to wear and advocate for rational dress, she and her cycling sisters had the power to advance dress reform, declaring,

“Miss Reynolds has made it ‘le premier pas.’ This girl of 16 has ridden in a costume suited to cycling. It is so inconspicuous that, without doubt, many persons who saw the rider failed to recognise her sex, and if lady cyclists begin on these lines the Rubicon will be crossed, and the aspirations of many ‘dress reforms’ advocates fulfilled in the complete emancipation of the weaker sex from the thrall of the petticoat…Thus, it seems to me not only possible, but highly probable that the reform in feminine dress will be started as a popular movement in the ranks of cycling…Miss Reynolds sets an example, and so long as a lady can ride well and mount gracefully I see no objection as all to the adoption by her of a suitable, eminently rational, and particularly safe costume, which relieves her once and for all of the flapping and dangerous skirt, which catches the wind, impeded the free action of the limbs, and every now and then has a pleasing trick of getting mixed up with the machinery. if practical female dress reform originates with cyclists I for one shall be delighted at the fact, and shall unhesitantingly claim the credit for our sport.”

Tessie’s place in the sporting news spotlight was short-lived. Her Brighton to London and back record held for about a year before being broken by another rider. Freeman’s Journal for 20 September 1894 reported that Miss E Wight of the Dover Road Club beat Tessie’s record with a time of 7 hours, 55 minutes, 46 seconds. By 1923 when Pearl Pratt set a new record, the time was already down to 5 hours, 45 minutes, 33 seconds. Little is documented about Tessie’s post-cycle racing life. She married Montague Main, with whom she had three children. Sadly, she outlived her husband and children. At some point in her adult life, Tessie relocated to London where she worked as a traffic safety warden, a job that in some ways channelled her earlier ambitions on the road as a champion cyclist.

One thing that we do know about Tessie is that she didn’t give up easily on the idea of rational dress. She remained committed to the dress reform movement, and continued to wear and promote rational dress in the years following her record breaking ride. Tessie was, without a doubt, as Hillier named her “the stormy petrel heralding the storm of revolt against the petticoat.”

Sources

Bicycling News, 1893-4

Freeman’s Journal, Sept 1894

Illustrated London News, Dec 1983

National Cycling Archive, Warwick