“Don’t cultivate a bicycle face.” — Don’ts for women on bicycles, New York World, 1895

“Don’t cultivate a bicycle face.” — Don’ts for women on bicycles, New York World, 1895

Medical professionals kept a watchful eye on cycling when it rose in prominence as a fashionable form of leisure for men and women in the 1890s. The health benefits and risks of cycling were a source of great debate, with doctors emerging on both sides of the issue. Pro- and anti-cycling camps presented a list of real and imagined cycling diseases and cures that reveals as much about social and gender attitudes as it does about the science and pathology behind these theories, especially in regards to the impact of women’s cycling.

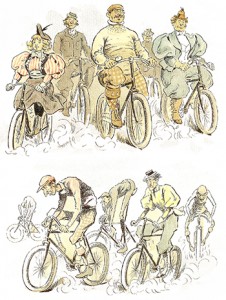

Bicycling ushered in a new era of physical leisure for women. Following on earlier leisure fads for light sport including lawn tennis and croquet, this late Victorian recreation continued trends in women’s outdoor recreation, but intensified the physicality and independence associated with it. Not surprisingly, women’s participation in cycling was a contentious issue. A number of doctors made women’s cycling health one of their specialisms and published widely on the subject, including Drs Arabella Kenealy, AT Schofield, Benjamin Ward Richardson, A Shadwell, EB Turner, Henry Garrigues and WH Fenton just to name a few. The 1890s were a time when women’s cycling was both censured and encouraged, with the body serving as the battlefield for a raging debate informed by gender conventions, social politics and anxiety about the changing role of women in a modernising world.

Bicycling ushered in a new era of physical leisure for women. Following on earlier leisure fads for light sport including lawn tennis and croquet, this late Victorian recreation continued trends in women’s outdoor recreation, but intensified the physicality and independence associated with it. Not surprisingly, women’s participation in cycling was a contentious issue. A number of doctors made women’s cycling health one of their specialisms and published widely on the subject, including Drs Arabella Kenealy, AT Schofield, Benjamin Ward Richardson, A Shadwell, EB Turner, Henry Garrigues and WH Fenton just to name a few. The 1890s were a time when women’s cycling was both censured and encouraged, with the body serving as the battlefield for a raging debate informed by gender conventions, social politics and anxiety about the changing role of women in a modernising world.

The Benefits of Cycling for Women

It wasn’t all bad news for lady cyclists during the cycling craze. Many doctors reassured their patients that the pastime could be taken up without concern if practiced in moderation. Prospective lady cyclists were encouraged to consult their physician to verify that they were fit and free of any underlying conditions that might be aggravated by cycling. As Patricia Vertinsky suggests in her book The Eternally Wounded Woman, this was more likely out of bias against women making their own decisions and deference to the opinions of male medical practitioners than out of real concern.

It wasn’t all bad news for lady cyclists during the cycling craze. Many doctors reassured their patients that the pastime could be taken up without concern if practiced in moderation. Prospective lady cyclists were encouraged to consult their physician to verify that they were fit and free of any underlying conditions that might be aggravated by cycling. As Patricia Vertinsky suggests in her book The Eternally Wounded Woman, this was more likely out of bias against women making their own decisions and deference to the opinions of male medical practitioners than out of real concern.

Medical professionals in favour of women’s cycling considered it harmless so long as overexertion, long rides, speed and accidents were avoided. Taking plein air exercise in peaceful settings was toted as an antidote to many of the diseases associated with the sedentary lifestyle of housewives, such as nervous disorders, dyspepsia and general languor. Dr WH Fenton, a Harley street physician, estimated that 90% of diseases afflicting Victorian women were “functional ailments, begotten of ennui and lack of opportunity of some means of working off their superfluous, muscular, nervous, and organic energy.” (Nineteenth Century, May 1896) Much later in the craze, cycling was championed as a healthy escape from the pressures of urban life and polluted factory air for working women.

Among the conditions cycling was credited with improving were cardio-vascular weakness, anaemia, gout, general invalidism, headaches, arthritis and consumption. In 1896, Queen magazine endorsed therapeutic cycling, writing that “we know one or two instances in which regular cycle exercise has effected a marvellous improvement when medical skill had been bailed.” For some, cycling cures became the new equivalent of the rest cure, a welcome alternative to the semi-incarceration of women suffering break-downs as described in Charlotte Perkins Gilmore’s 1892 story The Yellow Wallpaper.

By 1896, Lillias Campbell Davidson, cycling advocate and founding president of the Lady Cyclists’ Association, was confident enough that the anti-cycling movement was dead to state in Cycling Magazine that “It took doctors a long time to look with anything like a friendly, nay even tolerant eye, at women-a-wheel [but] we can afford to let he matter slip into the limbo of oblivion, since doctors have seen the error of their ways, and know better now.” Rather than slipping into oblivion as Davidson hoped, however, opinions against women’s cycling for medical reasons persisted until the end of the craze.

Bicycle Face and Other Cycling Diseases

The anti-cycling camp’s arsenal of medical and pseudo-medical ailments caused by riding was seemingly endless. Most of the medical rhetoric discouraging women’s cycling was related to the physical impact of riding, but sexuality, nervous disorders and mental health were also addressed. Physical disorders included skeletal deformities such as a curvature of the spine labelled kyphosis bicyclstarum or the cyclist’s hump shown right in the Punchcartoon “A Warning to Enthusiasts.” Other conditions ranged from serious cardio-vascular diseases such as tachycardia, to less threatening muscular overdevelopment, anemia and eyestrain. Rumours abounded on the Strand of actresses rendered mute by breathing too heavily while riding and dancers crippled by overdeveloped leg muscles. The cannon of cycling diseases includes mental and nervous conditions such as hysteria, neurasthenia, disorientation, sudden break-downs caused by stress, and tension due to the unconscious effect of constantly balancing. Ironically, many of these conditions were also listed as those aided by cycling in the opinion of other doctors.

The anti-cycling camp’s arsenal of medical and pseudo-medical ailments caused by riding was seemingly endless. Most of the medical rhetoric discouraging women’s cycling was related to the physical impact of riding, but sexuality, nervous disorders and mental health were also addressed. Physical disorders included skeletal deformities such as a curvature of the spine labelled kyphosis bicyclstarum or the cyclist’s hump shown right in the Punchcartoon “A Warning to Enthusiasts.” Other conditions ranged from serious cardio-vascular diseases such as tachycardia, to less threatening muscular overdevelopment, anemia and eyestrain. Rumours abounded on the Strand of actresses rendered mute by breathing too heavily while riding and dancers crippled by overdeveloped leg muscles. The cannon of cycling diseases includes mental and nervous conditions such as hysteria, neurasthenia, disorientation, sudden break-downs caused by stress, and tension due to the unconscious effect of constantly balancing. Ironically, many of these conditions were also listed as those aided by cycling in the opinion of other doctors.

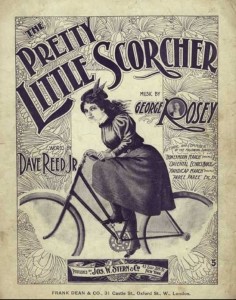

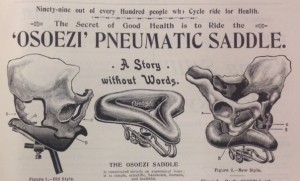

The reproductive system was often implicated medical problems associated with cycling. The saddle was the culprit in the case of pelvic inflammation, pressure on reproductive organs and the absorption of harmful vibrations. Cyclists were believed to be prone to uterine displacement, mal-menstruation, inflamed fallopian tubes, infertility and even chronic onanism through the aid of bicycle seats. Sexual impropriety was linked to cycling, not just in the form of as Dr Garrigues put it the “intimate massage” of the saddle, but by through its association with “fast” or “scorching” women, a double entendre suggesting loose sexual morals. Historian Jennifer Hargreaves writes in “The Victorian Cult of the Family and the Early Years of Female Sport” that cycling was viewed as an “indecent practice that could even transport women into prostitution.”(Hargreaves, in Gender and Sport, 2001)

The reproductive system was often implicated medical problems associated with cycling. The saddle was the culprit in the case of pelvic inflammation, pressure on reproductive organs and the absorption of harmful vibrations. Cyclists were believed to be prone to uterine displacement, mal-menstruation, inflamed fallopian tubes, infertility and even chronic onanism through the aid of bicycle seats. Sexual impropriety was linked to cycling, not just in the form of as Dr Garrigues put it the “intimate massage” of the saddle, but by through its association with “fast” or “scorching” women, a double entendre suggesting loose sexual morals. Historian Jennifer Hargreaves writes in “The Victorian Cult of the Family and the Early Years of Female Sport” that cycling was viewed as an “indecent practice that could even transport women into prostitution.”(Hargreaves, in Gender and Sport, 2001)

Cycling even brought women’s suitability for motherhood into question. Women were warned that cycling while pregnant would lead to foetal deformities, difficult labour, still births and an inability to breast feed, not to mention indicating that they were poor material for motherhood by exposing their unborn children to harm or death due to cycling accidents. In a sensational 1899 article entitled “Woman as an athlete” published in Nineteenth Century, Dr Arabella Kenealy projected that at its most extreme, by impeding reproduction and distracting women from motherhood for the pursuit of pleasure, cycling could lead to race suicide amongst middle class British and North American people of child bearing age who practiced it.

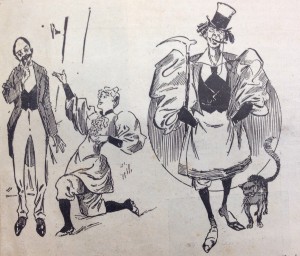

Linked to a woman’s reproductive role was the deleterious effect cycling was said to have on female beauty and figures. Those who failed to cycle in moderation were warned that they would develop muscular, mannish bodies and a masculine walk and posture. Complections lost their delicacy, grew red and ruddy with weather damage, and took on masculine features. The result, according to these warnings, was that women who cycled would be rendered unattractive to men, both physically and in their manners, thus damaging their marriage prospects. Satirical magazines such as Punch regularly ran comic illustrations showing lady cyclists mistaken for men, such as a vicar asking rational riders to remove their hats before entering a church in the manner of gentlemen, or acting as men such as the lady cyclists proposing to her emasculated suitor in the sketch shown right. An 1897 example from the CTC Gazette shown at the close of this post depicts a street urchin approaching a woman in cycling garb who he presumes to be a man, offering a box of matches and addressing her as “My Lord.”

Linked to a woman’s reproductive role was the deleterious effect cycling was said to have on female beauty and figures. Those who failed to cycle in moderation were warned that they would develop muscular, mannish bodies and a masculine walk and posture. Complections lost their delicacy, grew red and ruddy with weather damage, and took on masculine features. The result, according to these warnings, was that women who cycled would be rendered unattractive to men, both physically and in their manners, thus damaging their marriage prospects. Satirical magazines such as Punch regularly ran comic illustrations showing lady cyclists mistaken for men, such as a vicar asking rational riders to remove their hats before entering a church in the manner of gentlemen, or acting as men such as the lady cyclists proposing to her emasculated suitor in the sketch shown right. An 1897 example from the CTC Gazette shown at the close of this post depicts a street urchin approaching a woman in cycling garb who he presumes to be a man, offering a box of matches and addressing her as “My Lord.”

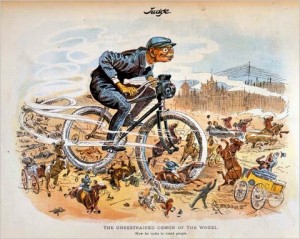

Surveying the abundance of literature on women’s cycling health dating to the late nineteenth century, one can not help but note the abundance of lurid cycling diseases invented during the craze. The most striking of these is the dreaded bicycle face. This hypothetical disease presented as an aerodynamic head with a pinched face, pointed nose, slack jaw, beady eyes, featured pulled back, and permanently frazzled expression. The disfigurement, which you can see an estimation of in the figure shown on the right above, was believed to be irreversible in some cases. You can listen to broadcaster Bridget Kendal and I discuss bicycle face on The Forum on BBC World Service.

Bicycle face afflicted men as well as women, as “The Unrestrained Demon of the Wheel” pictured left demonstrates. As a narrative of danger, however, it was a more effective deterrent for women since the implication of ruined beauty, respectability and hetero-normative prospects had far reaching consequences in the socio-economic context of the time. Dr A Shadwell, who claimed to have discovered and named “bicycle face,” diagnosed it as a symptom of tension and speed, noting that it was most common in women who scorched or rode in traffic. (National Review, February 1897) Critics of the lady cyclist set upon the bicycle face as emblematic of the physical and moral corruption that the pastime exacted on the fair sex. Dr Arabella Kenealy, a staunch opponent of the athletic woman, for example, lamented that in the case of a cyclist she was acquainted with “the charm she has lost in the suspicion of a bicycle face (the face of muscular tension)–was in communicable.” (Lady Cyclist, 1896)

Bicycle face afflicted men as well as women, as “The Unrestrained Demon of the Wheel” pictured left demonstrates. As a narrative of danger, however, it was a more effective deterrent for women since the implication of ruined beauty, respectability and hetero-normative prospects had far reaching consequences in the socio-economic context of the time. Dr A Shadwell, who claimed to have discovered and named “bicycle face,” diagnosed it as a symptom of tension and speed, noting that it was most common in women who scorched or rode in traffic. (National Review, February 1897) Critics of the lady cyclist set upon the bicycle face as emblematic of the physical and moral corruption that the pastime exacted on the fair sex. Dr Arabella Kenealy, a staunch opponent of the athletic woman, for example, lamented that in the case of a cyclist she was acquainted with “the charm she has lost in the suspicion of a bicycle face (the face of muscular tension)–was in communicable.” (Lady Cyclist, 1896)

Perhaps the most sensational of all imagined bicycling diseases was cyclemania. Cyclomania was defined as a chronic psychosis with symptoms similar to hysteria or kleptomania that afflicted women. Cyclomaniacs were described as being overwhelmed my an unnatural passion for cycling. They rode to often, too far, too fast and to a point of exhaustion. Victims of the disease were unilaterally obsessed with cycling. Wheelwoman described the condition as a compulsive disorder that compelled otherwise rational women to tackle every hill and left them with an insatiable appetite for speed. It was likened to an intoxication and addiction that left women dishevelled, shamed, lacking self-control, likely to engage in risky behaviour and generally behaving in an un-ladylike fashion not dissimilar to the chronically drunk woman. Maria Ward, author the 1896 guidebook Bicycling for Ladies warned that “scorching is a form of bicycle intoxication,” which once a taste for it was acquired, the body came to crave at exception of all else. It should come as no surprise that one of the signs that a woman had developed cyclomania was that she put cycling ahead of her family–a sure sign of an unhealthy infatuation in the Victorian mind.

Lurid disease-mongering reinforced the need for medical intervention in women’s

Lurid disease-mongering reinforced the need for medical intervention in women’s

cycling and coerced lady cyclists into practicing in moderation, if at all. Writing in Wheelwoman, Dr Turner commented that he felt the press over-represented cycling problems by reporting every accident, injury and ailment. He reassuring the public that “The bicycle-face, the bicycle-hand, the bicycle-foot are myths, and even ‘kyphosis bicyclostarum’ need but provoke a smile.” Narratives of medicalised cycle-danger were also disseminated in the press due to their commercial appeal. Companies such as saddle makers capitalised on fears of pelvic inflammation and other complications by advertising their products as designed with health and safety in mind, such as the Oesozi hygienic saddle shown right.

Medicalization and Liberty

From our comfortable position in the modern world, it is easy to look at Victorian stories about lady cyclists disfigured by the bicycle face with amusement as it takes its place amongst the latest internet memes. But, imposing medicalised limits on female cyclists was a very real and effective means of curtailing the freedoms and liberties born of the bicycle. Medical opinions of cycling as harmless if practiced in moderation gave women permission to ride if they adhered to physical and behavioural conventions, which while seemingly liberated also controlled the female body. Both sides of the debate co-opted science and pathology for power over lady cyclists through discourse about disease, health, exercise, sexuality, the family, space and even hygienic dress.

From our comfortable position in the modern world, it is easy to look at Victorian stories about lady cyclists disfigured by the bicycle face with amusement as it takes its place amongst the latest internet memes. But, imposing medicalised limits on female cyclists was a very real and effective means of curtailing the freedoms and liberties born of the bicycle. Medical opinions of cycling as harmless if practiced in moderation gave women permission to ride if they adhered to physical and behavioural conventions, which while seemingly liberated also controlled the female body. Both sides of the debate co-opted science and pathology for power over lady cyclists through discourse about disease, health, exercise, sexuality, the family, space and even hygienic dress.

The bicycle face was part of a wider discourse on the medicalization of women’s bodies, both in and out of the saddle, that was as much about gender and social politics as it was about women’s health and well being.

Selected Sources and Further Reading

“Don’ts for women on bicycles,” New York World. 1895.

Henry J Garrigues, A Textbook of the Diseases of Women. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1898.

Sheila Hanlon et al, “The Bicycle: Freedom Machine,” The Forum, BBC World Service. First broadcast October 2015.

Sheila Hanlon, “Bicycling Bodies: The Medicalization of Women’s Cycling,” in The Lady Cyclist: A Gender Analysis of Women’s Cycling Culture in 1890s London. PhD Dissertation, York University, 2009, pp 259-312. (Available on Proquest)

Jennifer Hargeaves, Sporting Females: Critical Issues in the History and Sociology of Women’s Sports. London: Routledge, 1994.

Arabella Kenealy, “Woman as an athlete,” Nineteenth Century. April 1899.

Sheila Scranton and Anne Flintoff (ed), Gender and Sport: A Reader. London: Routledge, 2002.

A Shadwell, “The Hidden Dangers of Cycling,” National Review. 1897.

“The Bicycle Face,” The Literary Digest. 7 September 1895.

Patricia Vertinksy, The Eternally Wounded Woman: Women, Doctors, and Exercise in the Late Nineteenth Century. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990.

Periodicals, c. 1895-1900

CTC Gazette

Nineteenth Century

The Lady Cyclist

The Lancet

The British Medical Journal

Wheelwoman