Adapting Women’s Dress to Early Cycling Technology, 1790-1860s

Fashion is one of the most popular topics in women’s cycling history. The Bicycle Fashion Files look at women’s cycling fashion across three eras, Early Inventions 1790-1860s, Highwheeling and Tricycling 1870-1880s, and The Cycling Craze 1890s. Part One begins with the early phase of cycling technology from running machines to early velocipedes.

Celeriferes and Draisienes: The Birth of Cycling Style

Cycling fashion trends evolved alongside developments in bicycle technology. Even as far back as the introduction of the celerifere in 1790s France, a running machine consisting of a wooden horse on wheels, what to wear while riding was a concern. These machines were popular with wealthy young gentlemen for park riding. For celerifere enthusiasts, the costume of choice was was a masculine military inspired jacket paired with matching breeches and cap.

Cycling fashion trends evolved alongside developments in bicycle technology. Even as far back as the introduction of the celerifere in 1790s France, a running machine consisting of a wooden horse on wheels, what to wear while riding was a concern. These machines were popular with wealthy young gentlemen for park riding. For celerifere enthusiasts, the costume of choice was was a masculine military inspired jacket paired with matching breeches and cap.

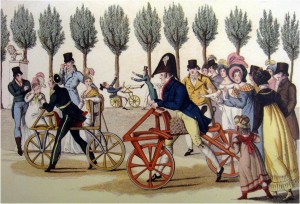

In 1817, German inventor Karl von Drais introduced an improved version of the running machine, which was popularly known as the draisiene or laufmaschine. This new machine was primarily marketed to men, but as you can see from the 1818 image of a demonstration in Luxembourg Gardens shown below, women were interested in this novelty and appeared in the crowd of spectators.

Von Drais took the unusual step of including a tandem with a seat for a female rider and a three wheeler for a solo female rider in his 1817-18 catalogue. Though no images of women riding these machines has survived, and there is no guarantee that they were produced, had women tried them they likely would have worn long gowns like those in attendance at the demo sport.

Von Drais took the unusual step of including a tandem with a seat for a female rider and a three wheeler for a solo female rider in his 1817-18 catalogue. Though no images of women riding these machines has survived, and there is no guarantee that they were produced, had women tried them they likely would have worn long gowns like those in attendance at the demo sport.

Denis Johnson’s Drop Frame Hobby Horse: High Fashion Cycling Gowns

Across the channel in London, Longacre based carriage maker Denis Johnson jumped into the bicycle business in 1818 with an improved version of the drassiene. His machine had larger wheels, a dipped frame to accommodate a comfortable saddle, iron forks and stays, and a handle bar. His customers were mainly men, and were stereotyped as dandies for the flamboyant outfits they wore, giving the machine the nickname “dandy horse.”

Across the channel in London, Longacre based carriage maker Denis Johnson jumped into the bicycle business in 1818 with an improved version of the drassiene. His machine had larger wheels, a dipped frame to accommodate a comfortable saddle, iron forks and stays, and a handle bar. His customers were mainly men, and were stereotyped as dandies for the flamboyant outfits they wore, giving the machine the nickname “dandy horse.”

Before long, Johnson devised a model for women. A reproduction of the machine held at the Science Museum is shown in the image above. The most striking feature of the ladies hobby horse is its drop frame. A description of it from The Liverpool Mercury noted, “The principle difference consists in the horizontal bar which unites the two wheels below instead of above, the drapery flows loosely and elegantly to the ground.” The details provided factor in not only the drop frame configuration, but its implications for dress.

What to wear while riding was already a key consideration for women. The fashion plate right shows a few more options in women’s cycling gowns from the hobby horse era. The dresses pictured do not depart significantly from the leisure gowns of the day. Note the bright coloured over dresses, long frilled hemline, and statement making bonnets. These were high fashion leisure outfits better suited to being admired than to riding.

What to wear while riding was already a key consideration for women. The fashion plate right shows a few more options in women’s cycling gowns from the hobby horse era. The dresses pictured do not depart significantly from the leisure gowns of the day. Note the bright coloured over dresses, long frilled hemline, and statement making bonnets. These were high fashion leisure outfits better suited to being admired than to riding.

The hobby horse was to be a short-lived fad. Riders soon tiring of bumpy uncomfortable rides, women’s riding was deemed lewd, and the Royal College of Surgeons declaring the machine to be the cause of chronic cramps and hernias.

Golden Age of the Velocipede: Daring Female Fashionistas A-Wheel

Cycling went into hibernation in the mid 19th century, aside from a few notable breakthroughs such as Scottish entrepreneur Kirkpatrick Macmillan’s claim to have invented a rear wheel driven bicycle in 1839. Things picked up again back in France with the invention of Pierre Michaux’s front wheel driven “pedal” bicycle in 1867. Fashionable types flocked to Michaux’s machines. Bicycle historian David Herlihy writes that “even upscale women, dressed in stylish gymnastic outfits, were turning up at the Michaux shop (which offered lessons) willing to try.”

Cycling went into hibernation in the mid 19th century, aside from a few notable breakthroughs such as Scottish entrepreneur Kirkpatrick Macmillan’s claim to have invented a rear wheel driven bicycle in 1839. Things picked up again back in France with the invention of Pierre Michaux’s front wheel driven “pedal” bicycle in 1867. Fashionable types flocked to Michaux’s machines. Bicycle historian David Herlihy writes that “even upscale women, dressed in stylish gymnastic outfits, were turning up at the Michaux shop (which offered lessons) willing to try.”

The image below shows a woman on an American Lallement velocipede. She wears a snug red jacket, short skirt, and striped bloomers. What is important to observe about this image is that it demonstrates that the formula of a short skirt over breeches was established as a solution to the problem of women’s cycling attire.

The image below shows a woman on an American Lallement velocipede. She wears a snug red jacket, short skirt, and striped bloomers. What is important to observe about this image is that it demonstrates that the formula of a short skirt over breeches was established as a solution to the problem of women’s cycling attire.

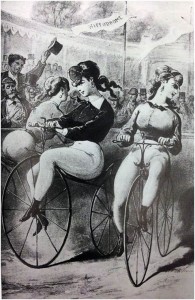

The 1860s and 70s also saw the emergence of women’s cycling as a popular form of entertainment. Women’s races at the Hippodrome in Paris attracted up to 15,000 spectators. Riders wore provocatively tight breeches or scanty gymnastic costumes, which was undoubtedly part of the attraction.

Well known diarist Arthur Munby attended a cycling performance by two female French velocipedests in the Royal Pleasure Gardens, Woolwich in 1869. Munby had a fetish for women in male garb, which is evident in his fixation on the cyclists’ breeches in his description of the evening. He wrote, “They were drest as men; in jockey caps and satin jackets and short breeches ending above the knee, and long stockings, and mid length boots. Thus clad, they stepped unabashed into the midst, and mounted their bicycles.” He continues with a dizzying description of how they threw their legs over the saddles, “pursuing one another round and round the hall, curving in and out…sometimes throwing one or both legs up whilst as full speed.”

Well known diarist Arthur Munby attended a cycling performance by two female French velocipedests in the Royal Pleasure Gardens, Woolwich in 1869. Munby had a fetish for women in male garb, which is evident in his fixation on the cyclists’ breeches in his description of the evening. He wrote, “They were drest as men; in jockey caps and satin jackets and short breeches ending above the knee, and long stockings, and mid length boots. Thus clad, they stepped unabashed into the midst, and mounted their bicycles.” He continues with a dizzying description of how they threw their legs over the saddles, “pursuing one another round and round the hall, curving in and out…sometimes throwing one or both legs up whilst as full speed.”

This was a voyeuristic, sexually charged opportunity to view women performing on the cycling track were not just their athleticism a-wheel was on display but also their bodies.

Conclusion

While it was still early days in cycling innovation, and women’s cycling remained uncommon, a few key trends in women’s cycling attire were established by the 1860s. Cycling was associated on one hand with wealthy, fashionable types chasing the latest leisure trends and dressing the part of respectable progressive women. On the other hand, it was connected to the transgressive culture of the women’s race track and stage where scantily clad women performed for the viewing pleasure of male voyeurs.

While it was still early days in cycling innovation, and women’s cycling remained uncommon, a few key trends in women’s cycling attire were established by the 1860s. Cycling was associated on one hand with wealthy, fashionable types chasing the latest leisure trends and dressing the part of respectable progressive women. On the other hand, it was connected to the transgressive culture of the women’s race track and stage where scantily clad women performed for the viewing pleasure of male voyeurs.

The need to adapt women’s costumes for cycling was recognised at a very early stage in the development of bicycle technology. One option was to alter the design of the bicycle, creating a drop frame compatible with conventional skirts and dresses. The other option was a new style of dress consisting of a short skirt over knee breeches, gymnastic outfits over tights, or that dispensed with skirts all together.

How best to resolve the problem of women’s cycling dress was a conundrum that persisted as bicycles continued to evolve. The next instalment of The Bicycle Fashion Files will trace the direction taken by cycling attire during the Highwheel and Tricycling age of the 1870s-80s.

Selected Sources and Further Reading

Caunter, CF. The History and Development of Cycles: As Illustrated by the Collection of Cycles in the Science Museum. London: Her Majesties Stationery Office, 1955-8.

Herlihy, David. Bicycle: The History. New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 2004.

Wosk, Julie. Women and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2001.