The Question of Women’s Dress During the Heyday of Tricycles and Highwheelers, 1870-1880s

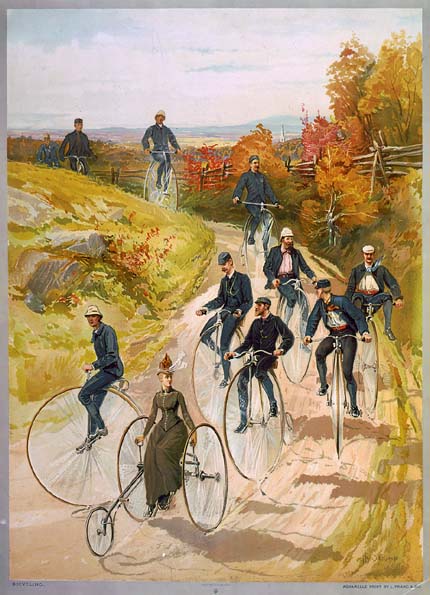

The second instalment of the Bicycle Fashion Files examines cycling dress in the age of the tricycle and highwheeler, 1870s-80s. While only a few women took to the pastime in those era, most of whom were wealthy or aristocratic with a handful of circus performers thrown in, the need for adapted dress was recognised. The results ranged from modest riding habits to scandalous gymnastic costumes on stage.

For earlier women’s cycling fashions, see Part One, Early Inventions 1790-1860. Later fashions are covered in Part Three, The 1890s Craze.

Dress Constraints and Conventions in the Golden Age of the Highwheeler

In the 1870s, the machine of choice among fit, young, men of means was the Ordinary, also known as the highwheeler, or penny farthing. Enlarging the front wheel of a velocipede to increase speed resulted in the lofty machine. The masculine traditions, physical demands, danger, and dress associated with high wheeling made the pastime off-limits for most women.

In the 1870s, the machine of choice among fit, young, men of means was the Ordinary, also known as the highwheeler, or penny farthing. Enlarging the front wheel of a velocipede to increase speed resulted in the lofty machine. The masculine traditions, physical demands, danger, and dress associated with high wheeling made the pastime off-limits for most women.

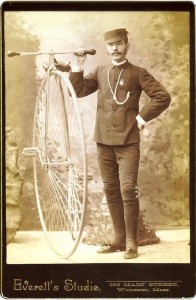

The customary attire for male cyclists was a militarised jacket, tight knee-breeches, and a cap or pith helmets, as reflected in the portraits shown above left. Cycling associations were especially fond of military influenced uniforms.

The riding habit worn by the lady tricyclist leading the pack in Hy Sandham’s painting at the top of this post, for example, would have been incompatible with the highwheelers her companions ride. Conventional women’s dress, and behavioural expectations, were not compatible with highwheeling. Politely straddling the saddle and front wheel in a dress was impossible, not to mention mounting which involved launching yourself onto the machine and the likelihood of a skirt catching dangerously (perhaps fatally) in the front wheel.

Nonetheless, a handful of women defied convention and tried the machines in borrowed breeches and gymnastic costumes. Shown right is an 1870s self-portrait of American photographer Francis Bernadette Johnson in the get up of a male penny farthing enthusiasts. Little is known about Johnson or her clandestine cycling habits, but one can imagine that if she was travelling at speed down a road on a penny farthing dressed in this costume, she would have been indistinguishable from typical cyclist to most passers-by. Carleton Reid has identified several more similar cases of women riders disguised as men on his website details Roads Were Not Built For Cars.

Nonetheless, a handful of women defied convention and tried the machines in borrowed breeches and gymnastic costumes. Shown right is an 1870s self-portrait of American photographer Francis Bernadette Johnson in the get up of a male penny farthing enthusiasts. Little is known about Johnson or her clandestine cycling habits, but one can imagine that if she was travelling at speed down a road on a penny farthing dressed in this costume, she would have been indistinguishable from typical cyclist to most passers-by. Carleton Reid has identified several more similar cases of women riders disguised as men on his website details Roads Were Not Built For Cars.

Equestrian Influences: Side Saddle Highwheelers and Riding Habits

In 1874, the Starley Co, a leading British bicycle manufacturer, tackled the problem of women’s dress by proposing a side saddle high wheeler for women, The Lady Ariel Ordinary, shown left.

In 1874, the Starley Co, a leading British bicycle manufacturer, tackled the problem of women’s dress by proposing a side saddle high wheeler for women, The Lady Ariel Ordinary, shown left.

This configuration mimicked the equestrian side-saddle position. So too did the rider’s costume, which is similar to a riding habit. Note the additional fabric at knee level to allow movement without revealing the form of the leg. The hem cut is long to hide the rider’s feet.

Accommodating women’s dress was a key considerations in this entirely impractical design.

Tricycle Mania Inspires Innovative Cycling Attire for Women

There was another option for women who wanted to ride: the tricycle. From the beginning, tricycling was considered a respectable pastime suitable for aristocratic ladies. Cycling fashion took off to meet the demand for elegant riding gear in the 1880s. Freedom of movement and mobility, coupled with dress decorum and full coverage while in motion, were key to these designs.

There was another option for women who wanted to ride: the tricycle. From the beginning, tricycling was considered a respectable pastime suitable for aristocratic ladies. Cycling fashion took off to meet the demand for elegant riding gear in the 1880s. Freedom of movement and mobility, coupled with dress decorum and full coverage while in motion, were key to these designs.

The tricyclist in blue, shown above right, wears a long billowing skirt constructed with ample flowing fabric to conceal her form. It appears to have an additional overskirt ruched up at the waist. A dark blue fitted jacket with 3/4 length arms and an oversized pink bowtie completed the look.

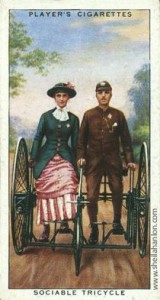

The Players cigarette card on the left features Mrs Welford, the first woman elected to the CTC in 1880. She is shown riding a Salvo Sociable with her husband, secretary of the club. Like the blue costume above it features an underdress, slim and pleated in two alternating pink printed fabrics in this case, and a pink ruched overskirt falling just below knee level. Welford’s jacket is CTC uniform green and is cut long for coverage while riding. Note how colourful and vibrant the costume is, in contrast with notions of Victorian drabness.

The Players cigarette card on the left features Mrs Welford, the first woman elected to the CTC in 1880. She is shown riding a Salvo Sociable with her husband, secretary of the club. Like the blue costume above it features an underdress, slim and pleated in two alternating pink printed fabrics in this case, and a pink ruched overskirt falling just below knee level. Welford’s jacket is CTC uniform green and is cut long for coverage while riding. Note how colourful and vibrant the costume is, in contrast with notions of Victorian drabness.

Despite the best efforts of designers, tricycle costumes were not quite fit for purpose. Cycle experts Viscount Bury and G. Lacy Hillier to commented in 1887 that “The dress was constantly riding up over the knees, each alternate stroke lifting it higher.”

Towards a Practical and Appealing Cycling Costume

Though tricycling skirts left something to be desired, designers had taken a serious interest in women’s cycling costumes and had advanced towards an outfit that married practicality with dress conventions. Innovations in women’s tricycling fashion set a precedent for the next phase of cycling to come: the Safety bicycle craze and the inventive marvels of fashion technology that went with it.

The cycling fashions of the 1890s will be traced in the next instalment of the Bicycle Fashion Files.

Selected Sources

Horace William Bartleet, Bartleet’s Bicycle Book, 1931.

Carlton Reid, Roads Were Not Built for Cars: How Cyclists Were the First to Push for Good Roads & Became the Pioneers of Motoring, 2015.

The Science and Society Picture Library, Science Museum, www.group.sciencemuseum.org.uk/business-services/picture-library

Julie Wosk, Woman and the Machine: Representations from the Spinning Wheel to the Electronic Age, 2003.