Innovation and experimentation in Late Victorian women’s cycling costumes

An explosion of women’s cycling fashion accompanied the cycling craze on the 1890s. The third and final blog in the Bicycle Fashion Files series looks at practical, popular and inventive approaches to late Victorian cycling dress.

The New Safety Bicycle

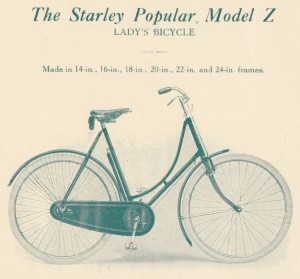

The introduction of the Safety bicycle in the mid-1880s ushered in a new era of popular cycling for men and women. With its low stature, diamond frame, two roughly equal sized wheels, and chain wheel rear drive The Safety was similar to the bicycle of today. A ladies’ drop frame was devised by lowering or removing the crossbar.

The introduction of the Safety bicycle in the mid-1880s ushered in a new era of popular cycling for men and women. With its low stature, diamond frame, two roughly equal sized wheels, and chain wheel rear drive The Safety was similar to the bicycle of today. A ladies’ drop frame was devised by lowering or removing the crossbar.

By the mid-1890s, cycling was a leading leisure trend among fashionable women and they needed the outfits to match their outdoor pursuit. Creating a costume that was practical, becoming and met dress conventions was a big ask – cycling manufacturers and clothing designers met this challenge through innovation and experimentation.

Skirted Riders

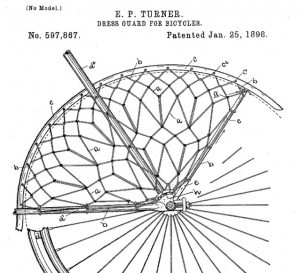

Cycle manufacturers, who had a vested interest in getting women on bicycles as consumers, found ways to adapt machines to conventional dress. Open, drop or step-through frames left room for full skirt. Skirt guards were added to moving parts to prevent loose fabric from snagging. Curvaceous single tube frames can be seen in the Hyde Park image shown above. Note the cycling outfits consisting of mutton sleeve jackets, full skirts, and sailor hats – in these cases the machine needed to be adapted to the fashionable dress worn on the promenade.

Cycle manufacturers, who had a vested interest in getting women on bicycles as consumers, found ways to adapt machines to conventional dress. Open, drop or step-through frames left room for full skirt. Skirt guards were added to moving parts to prevent loose fabric from snagging. Curvaceous single tube frames can be seen in the Hyde Park image shown above. Note the cycling outfits consisting of mutton sleeve jackets, full skirts, and sailor hats – in these cases the machine needed to be adapted to the fashionable dress worn on the promenade.

In the 1880s, lady tricyclists hit upon the practicality of riding in equestrian inspired cycling habits. These outfits consisted on a tailored jacket and skirt cut long in the front with a wide and square knee to accommodate a side saddle. Pioneering lady bicyclists, such as Helen Gladstone shown, here followed suit in the 1890s. When cycling, the cut of the riding habit allowed leg movement while concealing the appearance of feet in motion, a taboo by Victorian standards, and like horse riding provided full coverage right down to shoes when the rider’s knee was bent. It made the most of movement and modesty, and was visual reminder associating lady cyclists with aristocratic lady equestrians.

In the 1880s, lady tricyclists hit upon the practicality of riding in equestrian inspired cycling habits. These outfits consisted on a tailored jacket and skirt cut long in the front with a wide and square knee to accommodate a side saddle. Pioneering lady bicyclists, such as Helen Gladstone shown, here followed suit in the 1890s. When cycling, the cut of the riding habit allowed leg movement while concealing the appearance of feet in motion, a taboo by Victorian standards, and like horse riding provided full coverage right down to shoes when the rider’s knee was bent. It made the most of movement and modesty, and was visual reminder associating lady cyclists with aristocratic lady equestrians.

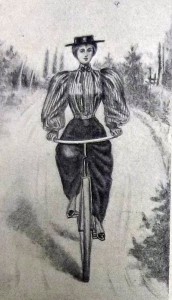

By far the most common approach to women’s cycling dress were active wear designs consisting of a skirt cut a few inches short in the style of a walking skirt. These skirts were generally constructed from sturdy tweed fabrics and paired with a Norfolk jacket, blouse and hat. Colours such as brown, grey, and dark green hid the dirt and dust cyclists were inevitably exposed to on roadways.

Inventions and Innovation

“Inventions” in dress constitutes a special category of wearable technology unique to the cycling era. Divided skirts were designed with a slit in the back to fit over wheels, often with buttons to do it up when off the bike. Skirts with built in bloomers provided an all-in-one costume that would not blow up to reveal the ladies’ figure. Skirts cut wide and deeply pleated allowed leg movement without showing it off to the public. Ankle clips, weights, and elastics were available to hold skirts in place a-wheel.

“Inventions” in dress constitutes a special category of wearable technology unique to the cycling era. Divided skirts were designed with a slit in the back to fit over wheels, often with buttons to do it up when off the bike. Skirts with built in bloomers provided an all-in-one costume that would not blow up to reveal the ladies’ figure. Skirts cut wide and deeply pleated allowed leg movement without showing it off to the public. Ankle clips, weights, and elastics were available to hold skirts in place a-wheel.

Among the more inventive designs were convertible skirts were that looked like normal active wear dresses when walking, but could be hiked up with pulleys, ropes, and buttons for riding. Alice Bygrave’s patented convertible cycling design shown left was a full length skirt that could be ruched up using a complicated system of sewn in cords to secure it out of the way when bicycling. There were also divided skirts that fell on either side of the wheel, often with a line of buttons running up and down the enclosure. It is noteworthy that so many patents for cycle wear were held by inventive women like Alice Bygrave in this era.

Innovation also applied to cycling underwear. Light woollen combinations, consisting of knitted vests and pantaloons were recommended for riders by companies such as Jaeger. Corsets were designed that fit higher on the hip, were looser, had wire instead of bone, and that were ventilated for greater freedom of movement while riding. The example shown right is a light weigh and breathable cycling corset from the V&A collection, circa the 1890s.

Innovation also applied to cycling underwear. Light woollen combinations, consisting of knitted vests and pantaloons were recommended for riders by companies such as Jaeger. Corsets were designed that fit higher on the hip, were looser, had wire instead of bone, and that were ventilated for greater freedom of movement while riding. The example shown right is a light weigh and breathable cycling corset from the V&A collection, circa the 1890s.

Rational Dress

There was another radical and solution to the problem of women’s cycling dress: rationals. Rational cycling dress was a modern take on the bloomers briefly popular in the US in around 1851. A range of styles were devised during the cycling craze. There were tailored tweed knickerbockers suits with knee-length breeches, bloomers designed to be concealed under skirts, bifurcated skirts, and billowing Turkish trousers.

There was another radical and solution to the problem of women’s cycling dress: rationals. Rational cycling dress was a modern take on the bloomers briefly popular in the US in around 1851. A range of styles were devised during the cycling craze. There were tailored tweed knickerbockers suits with knee-length breeches, bloomers designed to be concealed under skirts, bifurcated skirts, and billowing Turkish trousers.

The new style was a hit in France, especially among fashionable Parisian parks riders such as those shown in Jean Beraud painting of a scene in the Bois de Boulogne above. Soon, rationals were stocked in London’s finest West End boutiques and featured in fashion magazines. The editor of Queen was so enamoured with the new costume that she declared “the skirt…doom(ed) for active life.”

Female cycling athletes were among the earliest adapters of rational cycling dress. Teenager Tessie Renolds wore rational when she famously set the the Brighton to London and back record in 1893, completing the run in 8 hrs 38 mins. G Lacy Hillier heralded Tessie as a driving force in dress reform, writing in Bicycling News in 1893 that,

“Miss Reynolds sets an example, and so long as a lady can ride well and mount gracefully I see no objection as all to the adoption by her of a suitable, eminently rational, and particularly safe costume, which relieves her once and for all of the flapping and dangerous skirt, which catches the wind, impeded the free action of the limbs, and every now and then has a pleasing trick of getting mixed up with the machinery.”

Rational dress was as controversial as it was practical. Lady cyclists who wore the new  costume reported being insulted, pelted by rocks, and attacked in traffic. The Daily Mail called it a “disgusting costume” while letter writer in Lady Cyclist said it was “enough to make a bicycle blush under its enamel.” In 1898, Lady Harberton, founder of the Rational Dress League was famously turned away from the Hautboy Inn in Ockham, Surrey for wearing a knickerbocker cycling costume. Harberton is shown right in her outfit of choice for bicycle rides.

costume reported being insulted, pelted by rocks, and attacked in traffic. The Daily Mail called it a “disgusting costume” while letter writer in Lady Cyclist said it was “enough to make a bicycle blush under its enamel.” In 1898, Lady Harberton, founder of the Rational Dress League was famously turned away from the Hautboy Inn in Ockham, Surrey for wearing a knickerbocker cycling costume. Harberton is shown right in her outfit of choice for bicycle rides.

Rational cycling dress was quickly associated with the New Woman – all that was both praised and despised about her. As you can see from the Puck cartoon, at the bottom of this page, the cycling new woman was seen as stepping beyond accepted gender barriers and abandoning her role as wife and mother in favour of politics, education, and independence. Outrage at rationals was a direct attack on women’s mobility and an attempt to curtail the freedom and escape from the domestic sphere that the bicycle represented.

Rational dress was a favourite topic for satirical magazines such as Punch. In a well known cartoon from 1896, new woman Jessie enters the drawing room looking very proud as she shows off her brand new cycling costume. Gertrude confronts her, asking “My dear Jessie, what on earth is that bicycle suit for!” Jessie replied, “Why to wear of course.” A puzzled Gertrude exclaims, “But you haven’t got a bicycle!” to which the defiant Jessie responds, “No: But I’ve got a sewing machine!” Another example, “In Dorsetshire” deploys a clever play on words. The Fair Cyclist stopped on a road asks a passerby for directions, asking “Is this the way to Wareham, please?” The local assesses her cycling breeches, commenting “Yes, miss. You seem to me to have ‘em on all right.”

Rational dress was a favourite topic for satirical magazines such as Punch. In a well known cartoon from 1896, new woman Jessie enters the drawing room looking very proud as she shows off her brand new cycling costume. Gertrude confronts her, asking “My dear Jessie, what on earth is that bicycle suit for!” Jessie replied, “Why to wear of course.” A puzzled Gertrude exclaims, “But you haven’t got a bicycle!” to which the defiant Jessie responds, “No: But I’ve got a sewing machine!” Another example, “In Dorsetshire” deploys a clever play on words. The Fair Cyclist stopped on a road asks a passerby for directions, asking “Is this the way to Wareham, please?” The local assesses her cycling breeches, commenting “Yes, miss. You seem to me to have ‘em on all right.”

Lady cyclists ultimately succumb to public opinion and most opted for skirts over rationals for riding in 1890s Britain. The opprobrium rationals attracted on the road simply wasn’t worth it for women who wanted a leisurely cycle ride in the park, city, or countryside.

Conclusion

During it’s heyday from 1895-8, the cycling craze inspired great innovation in women’s dress. New designs for ladies cycling costumes took mobility into account in a way fashion never had before. Adaptations of women’s dress for cycling – from skirts shortened to avoid snagging, to convertible outfits going from practical to respectable with the tug of a pulley, to rational dresses allowing women to wear the breeches – reflected the new place women were beginning to occupy in society and in public spaces.

During it’s heyday from 1895-8, the cycling craze inspired great innovation in women’s dress. New designs for ladies cycling costumes took mobility into account in a way fashion never had before. Adaptations of women’s dress for cycling – from skirts shortened to avoid snagging, to convertible outfits going from practical to respectable with the tug of a pulley, to rational dresses allowing women to wear the breeches – reflected the new place women were beginning to occupy in society and in public spaces.

Women’s cycling fashions provide insight into how the acceptance, negotiation, and confrontation of gender conventions impacted everyday material culture in an era when tradition clashed with modernity.