Madame Sarah Grand posed with her bicycle, Kensington

Madame Sarah Grand posed with her bicycle, Kensington

In addition to being one of the leading literary figures of her time Sarah Grand was, in keeping with the idea of the New Woman she promoted, an avid cyclist.

Born Frances Elizabeth Bellenden Clarke in 1854, Grand spent her early years in Donaghadee, Northern Ireland. She had an idyllic childhood, growing up near the sea. Following the death of her father in 1862, however, the family who were of English decent, relocated to England.

Frances’ feminist leanings were evident from an early age. In 1868, she was expelled from the Royal Navy School, Twickenham for protesting in support of Josephine Butler’s anti-Contagious Diseases Act movement. She was swiftly shipped off to finishing school in Kensington. Looking back on her schooling in an 1897-8 interview with The Young Woman, Grand summed up her education as “most desultory.”

Aged only 16, Frances married 39 year old widowed army surgeon David Chambers McFall, already the father of two sons. She soon found herself trapped in an unhappy marriage with a son of her own, David Archibald Edward McFall. Life as a surgeon’s wife exposed Frances to the epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases and the deplorable conditions faced by prostitutes sent to lock hospitals for the treatment of STDs. She developed an interest in medical science, though its philosophy appealed to her more than its practice. The couple travelled widely including visits to the Straits Settlements, China, and Japan on a tour of the Far East from 1873-8. A young Grand is shown in the portrait to the left.

Her marriage may have been a trial, but her experiences informed her writing, from her warnings about syphilis in The Heavenly Twins, 1893 to the critique of marriage and the sexual double-standard that resonates through much of her work. An example of her views can be found in “The Modern Girl,” The North American Review, 1894. Biographical details about Grand can be found in the many interviews she gave with the popular press, such as the one from The Young Woman shown below.

Writing was to be her way out of her marriage. A modest income as an author gave Frances the financial independence needed to leave McFall. Her first novel Ideala, following one women’s deliberations about abandoning her husband for another man, was published in 1888. Two years later, her own divorce became a reality.

Frances moved to London and reinvented herself under the pen name Madame Sarah Grand, a title that embodied the New Woman ethos and distinguished her from the female writers of her time published under male pseudonyms. Grand is best known for popularising the term “New Woman”, which appeared in The Heavenly Twins in 1893, “The New Aspect of the Woman Question” North American Review in 1894, and an 1894 debate with Ouida (novelist Maria Louise Ramé).

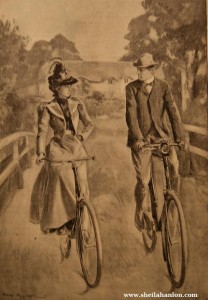

The bicycle was to become a symbol of Grand’s New Woman. Popular representations of the politically progressive, well-educated, literate, independent girl of the period often depict her as a cyclist. In her work on fin-de-siècle women and transport, scholar Sarah Wintle suggests that a mastery of horses, and later bicycles and cars, was associated with power and individualism, making cycling an essential hobby for New Women.

In addition to her literary contribution to the woman question, Grand actively supported women’s suffrage. She was a member of the Women Writers’ Suffrage League, Women’s Citizens’ Association, Women’s Suffrage Society, and Tunbridge Wells NUWSS. She served as one of the WWSL banner bearers at the mass NUWSS meeting held 13 June 1908 in Hyde Park.

Grand’s exposure to cycling dates to the early 1890s. She was already an expert cyclist by 1896 when The Hub published ” A Chat with Sarah Grand—Woman of Note in the Cycling World.” The following year, Lady’s Realm included Grand in their feature on “Some Famous Lady Cyclists.” Grand posed for the portrait with her bicycle outside her Kensington home shown above, which was published in The Young Woman article shown right.

In addition to riding for pleasure and exercise, Grand championed cycling for the opportunities it offered women and as a form of healthy excercise The benefits of cycling for women was one of the topics Grand addressed on a lecture tour of the US. At the same time, she was wary of the draw backs of too much cycling, such as ruining fair complexions.

FM Gardiner’s 1896 article for Cycling World Illustrated, “Chats with Cyclists: Madame Sarah Grand,” provides insight into Grand’s cycling experiences and philosophy. Grand reveals that she learned to ride at a cycling academy in Paris, away from the prying eyes of society. The magazine suggested this was “a hint which might be taken with advantage by English ladies, who too often struggle on public roads with refractory machines, apparently unconscious that they are objects of ridicule to their neighbours.”

“I had no idea of riding,” said Madame Grand, “till I accompanied a friend who was about to take a lesson at one of the establishments founded in Paris for the purpose. There I saw women of all ages, sizes, and weight managing their bicycles with perfect facility, and evidently enjoying exhilarating exercise.”

Back in England, Grand took regular short rides of up to four or five miles, which she found to be “sufficient for exercise without fatigue” and a healthy complement to the course of Salisbury treatment she followed. Healthy outdoor exercise was one of the chief attractions of cycling for Grand. This was something she felt all people could benefit from, not just the young. “When circumstances are favourable, women, particularly in middle life, are inclined to be indolent, and prefer their fireside to active pursuits out of doors,” she noted, adding “regular exercise in the open air is unfavourable to flabbiness” and “cycling offers a means of procuring at a nominal cost exhilarating exercise.”

On the issue of rational dress, Grand commented, “In Paris I always rode in a costume of this description, and those who know anything of cycling are convinced of its comfort…but in this country I use a skirt which attracts less notice.” Grand believed there was a “considerable fortune” waiting to be had in designing a practical women’s cycling costume. Her specifications were for a light waterproof garment that allowed natural movement and accentuated the “good points” while concealing the “less pleasing.” She was critical of the cuts available in London that “convert the wearers into caricatures and are appalling to the cultivated eye and taste.”

Cycling fit the image of the New Woman that Grand cultivated in her novels, articles, and lectures. It seems only natural that a key inventor of the New Woman ideal should have been a cyclist herself.

Nothing, not even dress, could hold back Grand’s modern woman. She told Cycling World that “The New Woman has too much healthy enjoyment of life to worry about whether her ankles are visible or not. Besides, she has such good ones—and naturally she knows it.”

Post script: In 1920, Grand moved to Bath where she served as lady Mayoress for several years. She died in 1942 in Calne, Wiltshire.

Selected Sources:

“A Chat with Sarah Grand—Woman of Note in the Cycling World,” The Hub, 1896.

“Chats with Cyclists: Madame Sarah Grand,” Cycling World Illustrated, 1896.

Grand, Sarah. The Heavenly Twins. London: Heinemann, 1893.

Grand, Sarah. “The Modern Girl,” The North American Review, 1894.

Heilman, Ann. New Woman Strategies: Sarah Grand, Olive Schreiner, and Mona Caird. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004.

“Madame Sarah Grand At Home,” The Young Woman, 1897-8.

“Some Famous Lady Cyclists,” Lady’s Realm, Sept 1897.

Wintle, Sarah. “Horses, Bikes and Automobiles: New Women on the move,” in Angelique Richardson ed The New Woman in Fiction and Fact: Fin de Siècle Feminism. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.

Pingback: Wheelwomen | Sheila Hanlon