Frances Evelyn ‘Daisy’ Greville, The Countess of Warwick

Frances Evelyn ‘Daisy’ Greville, The Countess of Warwick (1861–1938) was one of late England’s leading Victorian and Edwardian socialites and philanthropists. It is, however, for her role as royal mistress and subject of society gossip that she is best remembered. As both a progressive woman and follower of fashion, Daisy, as she was commonly known, learned to cycle early in the craze. Cycling magazine identified The Countess of Warwick as “among the first ladies who caught that rabid disease commonly known as cyclomania.”

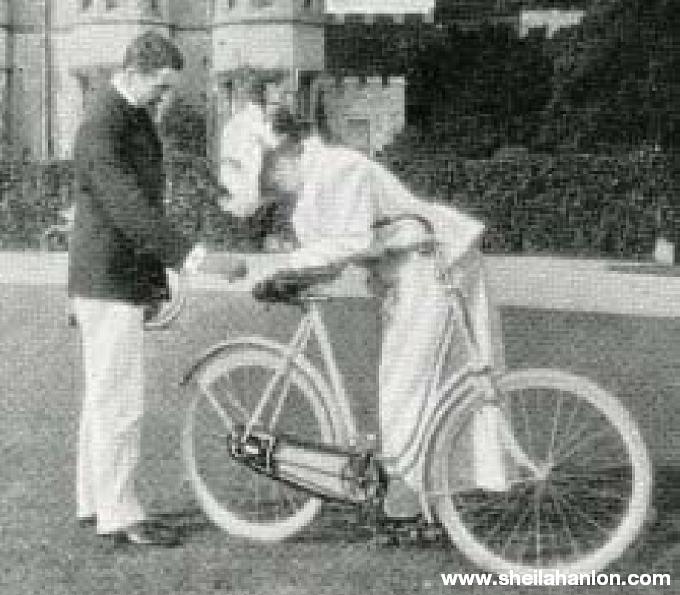

The image right shows Daisy with her bicycle and her brother, Lord Rosslyn. The picture was likely taken at Easton Lodge, her hereditary manor in Essex which was one of her preferred places to cycle. It is also where she was born 1O Dec 1861, daughter of Colonel the Right Honourable Charles Maynard and his second wife Blanche Fitzroy. Charles Maynard inherited the estate that was handed down to his three year old daughter Daisy upon his early death.

The image right shows Daisy with her bicycle and her brother, Lord Rosslyn. The picture was likely taken at Easton Lodge, her hereditary manor in Essex which was one of her preferred places to cycle. It is also where she was born 1O Dec 1861, daughter of Colonel the Right Honourable Charles Maynard and his second wife Blanche Fitzroy. Charles Maynard inherited the estate that was handed down to his three year old daughter Daisy upon his early death.

The young Daisy was considered a potential spouse for Queen Victoria’s son Prince Leopold, but the pairing did not work. Instead, she married Francis Greville, Lord Brooke in 1881. Greville inherited an Earldom from his father in 1893, at which point the family moved to Warwick Castle. Warwick Castle soon became known for its society gatherings with Daisy as hostess.

The Greville marriage was an unhappy one from the start. Lord Brooke was reputed to be a cold man who pursued other women on the side. Daisy was no better. She was involved in affairs with a number of prominent men, most famously Albert Edward, The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII. An earlier affair with Lord Charles Beresford ended badly when Daisy discovered that he was expecting a child with his wife. An enraged Daisy sent a threatening letter to Lady Beresford which ended up in a society lawyer’s hands for safekeeping.

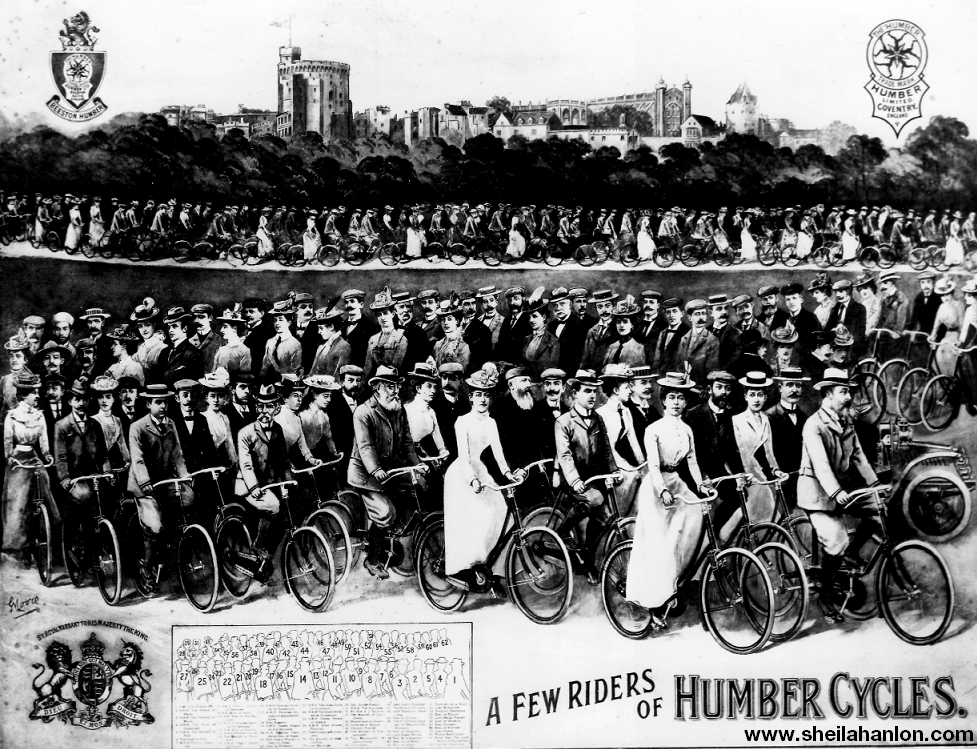

The Prince of Wales intervened out of sympathy for Daisy, and petitioned Beresford to destroy the letter. It was around then that Daisy’s relationship with the future king began, an affair that would last until 1898. As an aside, Albert Edward was himself a keen cyclist and featured in the Humber ad shown below.

After the collapse of her affair with The Prince of Wales, Daisy took up with wealthy bachelor Joseph Haydock, with whom she had two children despite the fact he was also seeing the wife of the Marquess of Downshire. Later in life, Daisy fell on hard times and attempted to blackmail the royal family by publishing intimate letters written to her by Edward VII. The plot failed when it was determined that the copyright belonged to the king.

Daisy’s scandalous personal life has overshadowed her contribution to politics and philanthropy. Women’s rights were one of her key concerns. Cycling noted that “With no uncertain sound does Lady Warwick speak of women’s suffrage.” She was also interested in improving the lives of workers and rural people and wrote on issues such as unemployment.

She founded the Studley Agricultural College for Women, shown left, in 1898 and a needlework school at Easton. She also volunteered her home as a venue for meetings about causes she supported, including trade unionism. In 1904, she joined the SDF, and after WWI she became a member of the Labour party.

She founded the Studley Agricultural College for Women, shown left, in 1898 and a needlework school at Easton. She also volunteered her home as a venue for meetings about causes she supported, including trade unionism. In 1904, she joined the SDF, and after WWI she became a member of the Labour party.

Daisy took a particular interest in socialism following a confrontation with Robert Blatchford, editor of The Clarion. In an 1895 edition of his paper Blatchford criticized her extravagant lifestyle, citing as an example the lavish party held at Warwick Castle to celebrate Lord Brook’s inheritance of the title Earl. Blatchford condemned it as a show of “aristocracy’s conspicuous consumption” while other people starved and toiled, “their souls crushed between ever-grinding millstones.” Daisy visited him at his London office to extract an apology, but got a lecture instead. In the end, he won her over.

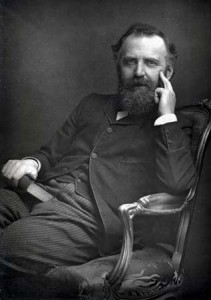

Daisy also credited WT Stead, shown left, with her political awakening. Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette from 1883-9 and founder of the Review of Reviews in 1890, was a pioneering investigative journalist. He is best known for “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon,” an 1885 serial tracking child prostitution to the point of purchase. The incident landed him in jail, but saw the age of consent for women raised from 13 to 16. Stead supported women’s rights and had a large network of female friends, including influential writers and political campaigners such as Daisy.

Progressive politics and sympathy for the downtrodden were not the only interests Stead and Daisy shared. Stead was an enthusiastic cyclist who founded a women’s cooperative bicycle club, the Mowbray House Cycling Association (MHCA). Daisy was one of a number of influential women who supported the group, the objective of which was to make bicycles accessible to working women who could not otherwise afford them. Warwick understood the liberating potential of cycling for these women, and once told Stead “I have daily got on my bicycle and sped away for air and exercise and all kinds of adventures.” Interestingly, the author of the Cycling article on Warwick, Miss NG Bacon, was Stead’s personal secretary and an MHCA organiser.

The Countess of Warwick was an early adapter of the bicycle. Cycling magazine reported that, “her first machine was a convertible tricycle-bicycle with which she used to cycle along the broad paths of Easton Park. So enthusiastic a devotee did Lady Warwick become of the pastime of cycling that, on leaving Warwick Castle to spend some weeks at Easton, her horses and carriage were left in solitude, whilst she was to be seen gaily devoting herself to that marvelously wrought ‘toy of steel.’ However we may look at it, it must, indeed, be considered a very high compliment for a lady, so fond as Lady Warwick is of driving spirited horses, to fall in love with the cycle.”

The Countess of Warwick was an early adapter of the bicycle. Cycling magazine reported that, “her first machine was a convertible tricycle-bicycle with which she used to cycle along the broad paths of Easton Park. So enthusiastic a devotee did Lady Warwick become of the pastime of cycling that, on leaving Warwick Castle to spend some weeks at Easton, her horses and carriage were left in solitude, whilst she was to be seen gaily devoting herself to that marvelously wrought ‘toy of steel.’ However we may look at it, it must, indeed, be considered a very high compliment for a lady, so fond as Lady Warwick is of driving spirited horses, to fall in love with the cycle.”

Daisy also rode in London, joining the promenade of elite park riders during the season. In her 1947 autobiography Links in the Chain of Life, Baroness Orczy recalled seeing Daisy during cycling craze, writing, “in the late ‘nineties the great thing in London was to go and watch the bicycling in Battersea Park. After tea-time the park was thronged with all the smartest women in London. I remember seeing the beautiful Lady Warwick there on occasion, most exquisitely dressed.”

Wheelwoman magazine looked to The Countess of Warwick as a cycling trend setter, noting in 1897 for example that she painted her bicycle seasonally: pale green for spring, white for summer, and brown for autumn.

On the question of dress, it seems that Daisy entertained the idea of rational cycling costumes, though she did not wear the new style herself. Cycling commented, “last summer, whilst the whole world–the Cycling Press included–was shrieking against Wheelwomen having freedom of choice in regard to their apparel the Countess of Warwick was showing, at Eastnor, to a few knickerbockered damsels how refreshing it is, after a long day’s cycle, to have tea with one of the most fascinating hostesses in the land.” Given the familiarity Bacon wrote about the event with, and the rational dress code in effect, this may well have been a group of MHCA riders or another women’s bicycle club.

Despite the popular obsession with Daisy as a belle of the cycling world, few images of her riding have survived. When she appeared on the cover of Cycling World Illustrated’s inaugural issue in 1896, it was without her bicycle. The magazine chose a traditional portrait of her posed in a chair wearing an delicate white gown and holding a fan in her lap. The picture of Warwick and her bicycle at Eastnor shown above is one of the pictures showing her as a cyclist identified to date. It comes from her 1931 autobiography Life’s Ebb and Flow, which, coincidentally, does not mention cycling at any point in the text.

Further evidence that Daisy may not have been quite the cycling enthusiast she was reputed to be comes from an 1896 article in the Tuapeka Times. This American publication claimed that, “Lady Warwick says she is not at all enamoured of this form of exercise; she thinks that women, as a rule, look far from well on bikes, and she dislikes the necessity of wearing a special dress, which is, least of all others, calculated to set off the perfections of the female form divine–especially when the form in question by no means approaches the stature of a man.”

But, the bicycle was not without its saving grace for Daisy. The Tuapeka Times continued, “she finds the bike, however, very useful in the country, for she can go on it distances which would be utterly impossible by any other mode of conveyance. For this reason, therefore, and for no other, she is in favour of biking.”

The value of the bicycle to rural populations, both aristocratic estate owners like Daisy and her poorer country neighbours, is something Cycling picked up on too. “Cycling, indeed, may do a little towards the return of the good old days,” the magazine wrote, “when country houses will be revived by the presence of troops of joyous wheel-folk…in this way, some of the wealth lost to villages may be returned in a way the Countess of Warwick little suspected when she first mounted her cycle.” If she wasn’t aware of the benefit of cycling to the countryside early in her life, she had come to this conclusion by 1931 when she wrote Afterthoughts, in which she identified the bicycle as a boon to the rural labouring poor.

Cycling may have come to mean little to The Countess of Warwick later in life, but there is ample evidence suggesting that she enjoyed the pastime at the height of its popularity. Daisy was so central to cycling culture that she is popularly believed to have inspired Harry Dacre’s 1892 comical song “Daisy Bell” about a bicycle made for two. You can read more about Daisy and this music hall favourite in an earlier post, “A Bicycle Built for Two.”

Frances Evelyn ‘Daisy’ Greville, The Countess of Warwick was certainly one of the leading bicycle belles of her time.

Selected Sources

“Womenly Women Who Cycle: The Countess of Warwick,” Cycling, 1895.

“A Distinguished Lady Cyclist: The Countess of Warwick,” Cycling World Illustrated, 1896, Cover.

Greville, Frances Evelyn, The Countess of Warwick. Life’s Ebb and Flow, 1931.

Greville, Frances Evelyn, The Countess of Warwick. Afterthoughts, 1931.

Anad, Sushila Daisy: The life and loves of the Countess of Warwick, 2009.

Was Ms. Greville Francis Evelyn, The countess of Warwick married to John Boyd Dunlop the inventor of the pneumatic tyre?